By William Wood, Foyle Special Collections Library, King’s College London

As Special Collections librarians, we have an understanding that the collections we hold are just that. Special.

This could be due to their age, uniqueness or rarity, their provenance or history of prior ownership, the nature of their contents or their historical or cultural significance. While we recognise that our collections hold many particularly special items, we can’t possibly know all of the intimate details of each and every volume in our collection of over 200,000 items. Our role, first and foremost, is to provide access to those who have the insight to recognise what it is that we hold in our hands.

In January 2024, Martin Williams, Australian historian, contacted our staff at the Foyle Special Collections Library with an extensive enquiry about an item in our collection that we were to learn ticked all the boxes above. The following is an excerpt:

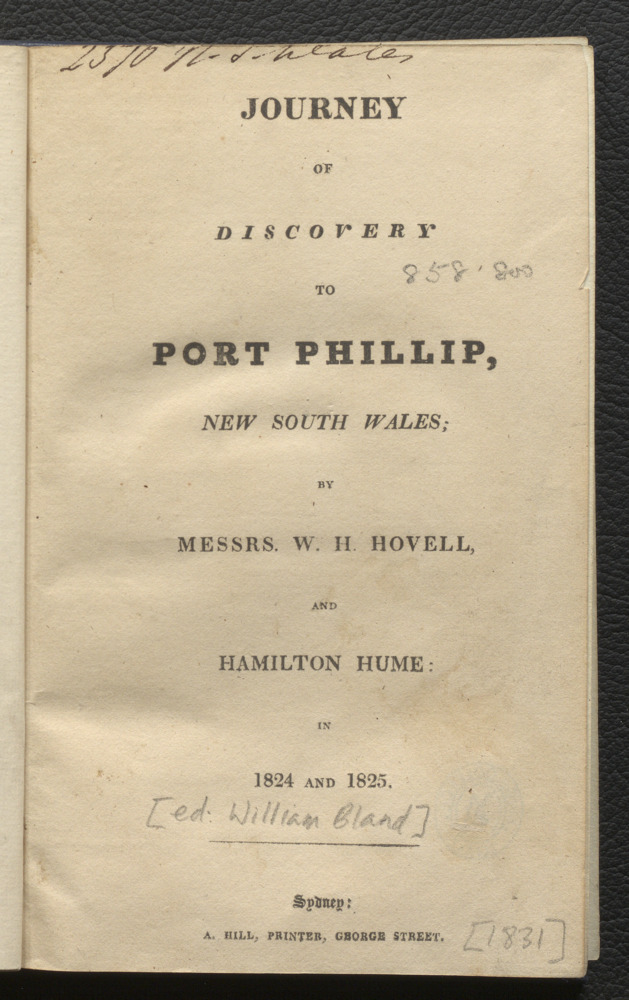

‘You have a book that you have recorded as: Journey of discovery to Port Phillip, New South Wales, by Messrs. W.H Hovell and Hamilton Hume, in 1824 and 1825. Great Britain. Colonial Office Library, former owner.; Bland, W. (William)

Can you tell me when that book was received by the Colonial Office and who sent it to them? It might be contained in notes that you record as existing at the start of the book.’

After fetching the item in question from storage we responded with the following, along with links to other institutions who held complimentary material:

‘Our copy is recorded as being re-bound in 1978 and has annotations as follows:

In later pencil hand (e.g. written when it had been re-bound) Ferguson 1423 extremely rare.

Another copy given to the Royal Empire Society – this became the Royal Commonwealth Society, and it looks like this copy is available as part of Cambridge University’s holdings.

At the head of the title page in our volume and written in contemporary-to-publication hand is ‘2370 NS Wales’. We think (because of the relative lowness of the number) that it came to the Colonial Office Library around the time it was printed. It was likely placed here by someone who worked for the Colonial Office. As you spotted from the catalogue record, the name of former owner, William Bland, is written on the title page and listed as the editor, with the year 1831 also written on.

There are also a very small number of ink corrections/crossings out in the copy we hold.’

What followed were several emails that clarified details, expanded on points of interest and highlighted for us the importance of this text to Australian history. As such, we sent the item away for conservation and cleaning, requesting that the item be resewn and repaired as needed within its existing binding.

Continuing our collaborative research, we deduced that ‘Ferguson 1423’ referred to a listing in Ferguson’s Bibliography of Australia. Further to this, Martin Williams was able to confirm for us that the copy we held was most likely delivered as part of a large and important dispatch sent by the Governor of New South Wales, General Sir Ralph Darling, to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Sir George Murray, Colonial Office, London, and dated 28th March 1831. This dispatch contained our item, along with a set of 21 plans by the New South Wales Surveyor-General, Thomas Livingstone Mitchell.

Martin thanked us for our assistance and revealed to us that he was in fact the living authority on the journey made in 1824 by the explorers Hume and Hovell. He confirmed that by digitising and making accessible our copy of William Bland’s revised retelling of their expedition, we would be contributing to the documentary heritage of the region that later became the state of Victoria.

***

In 1824, then Governor of New South Wales, Sir Thomas Brisbane, commissioned both Hovell and Hume to lead an expedition that intended to explore the land between Lake George and Bass Strait, following the course of uncharted rivers.

William Hovell was born in Yarmouth, Norfolk on 26 April 1786 and at only 10 years of age began a career at sea. By his early 20s he had risen through the ranks to command a trading vessel in South America before deciding to emigrate to Australia with his wife and two children. Though Hovell had little experience of surviving in the harsh environment of the Australian bush, he had been earmarked for Governor Brisbane’s expedition due to his practical navigation skills.

![A posed photograph of Capt. William Hilton Hovell. He sits in an ornate chair dressed smartly in a suit with bow-tie. Photo by Oswald Allan [sic], 360 George, Sydney, July 1871. Accompanied Hamilton Hume in exploratory journey to Port Philipe [sic], Oct. 1824. -- in ink on the reverse](https://blogs.kcl.ac.uk/kingscollections/files/2024/09/Captain-William-Hilton-Hovell-explorer-July-1871-photographer-Oswald-H-Allen.jpg)

Though the official plan to chart the rivers did not eventuate, Hovell and Hume decided to fund their own journey, supported and furnished with some supplies by the Government, they set out exactly 200 years ago in October of 1824, in the hopes of finding new grazing land for the burgeoning colony.

On October 3rd, the small party of eight men left Hume’s farm at Appin and headed south to his sheep station near Lake George. This would be the starting point of a journey that would span the next four months and over 1000 miles across harsh and unforgiving terrain.

Both Hume and Hovell were furnished with skeleton maps that marked the coastline of south-east Australia but were otherwise blank, with instructions from Governor Brisbane to track their daily progress using the navigational tools they had at their disposal including sextant, compass and perambulator. The men also kept small field notebooks that detailed their trials and tribulations, and it would be these documents that would be edited by William Bland into the Journey of discovery to Port Phillip that we now hold in our collections here at King’s.

The landscape described by Hovell was rough and mountainous, carved by swift flowing rivers and choked with impenetrable scrub. He and Hume often argued about the best pathway through this forbidding country, with Hovell leveraging his navigational prowess against Hume’s superior knowledge of the Australian bush. An article published in the Sydney Morning Herald states that:

‘The explorers argued and wrangled all the way, at times separating when they couldn’t agree. An instance when two heads were worse than one! They travelled (the hard way and the wrong one) over some of Australia’s most rugged country, through nerve-shattering gorges and over swollen rivers.’

They might have disagreed regularly on the direction to take but were unified in their appreciation for the animals they had brought with them. Their prized hunting dogs were essential in supplementing their dwindling rations with the fresh meat of kangaroo and waterfowl, with Hovell documenting the many kills they made, the injuries they sustained, and the low points faced when having to feed the dogs on boiled flour when food supplies ran almost dry. It was the bullocks they brought however, that made the journey even remotely possible. In his revised edition of their journals William Bland confirms that:

‘Never was the great superiority of bullocks to horses (in some respects) for journeys of this description, more observable than in the progress of this dangerous and difficult descent…The horse is timid and hurried in its action…the bullock is steady and cautious.’

6 November 1824

Accidents can and did happen over the course of their expedition and each was duly noted in their journals. Reading through these passages myself, I was taken aback by the matter of fact retellings of incidences like the following:

‘In effecting the descent from these mountains, they had nearly lost one of the party, as well as a bullock; the animal had fallen when it had reached about two thirds down the mountain, in consequence of the slipping of a stone from under its feet, and in its fall, it had forced down with it, the man who was leading it. But their fall was intercepted by a large tree, and the man, as well as the animal, was thus prevented from being dashed to pieces. The man, however, unfortunately, was much hurt.’

6 November 1824

Journal entries such as these show the land to be unforgiving and inhospitable and yet, Hovell regularly recorded interactions with local Indigenous groups who appeared not only to survive but to thrive in this challenging environment. He observed their numerous methods of food gathering, of land management such as back burning and the damming of rivers for fish traps. At a time now known as the frontier war period, when tensions between white settlers and the traditional owners of the land culminated in numerous massacres of local populations, Hovell expressed rare respect and even envy for the life they led with one journal entry stating:

‘Those are the people we generally call “miserable wretches,” but in my opinion the word is misapplied, for I cannot for a moment consider them so. They have neither house-rent nor taxes to provide, for nearly every tree will furnish them with a house, and perhaps the same tree will supply them with food… They are happy within themselves; they have their amusements and but little cares; and above all they have their free liberty.’

29 November 1824

A liberty that was to be increasingly encroached upon into the mid nineteenth century by the advancement of the spreading colony.

***

Hovell and Hume overcame many challenges during their journey and in doing so, disproved the belief, commonly held by British authorities and perpetuated by surveyor John Oxley, that the interior of the country was a marshland that bordered the edges of a vast inland sea. In keeping west of the Great Dividing Range, they had instead found abundant pasture and fertile agricultural land as they rounded out their expedition in Corio Bay, on the Victorian coast, where present day Geelong is situated. Hovell mistakenly believed they had arrived at Westernport, their initial goal, and did not realise their mistake until much later, which was to have a follow-on effect through the ages that he could not have anticipated.

Returning to the starting point of their journey by January 1825, Hume and Hovell reported their discoveries to Governor Thomas Brisbane, incorrectly stating that they had indeed arrived in Westernport. The ‘successful’ expedition was touted by Hume in several newspaper articles and repeated by a certain William Bland, editor of the book we hold in our collection that was the starting point of this blog post.

Bland published a number of articles corroborating their claims as part of the promotion he was doing for that very same book. It was not until 1827, two years later, that a sailing party, including Hovell, was sent along the coast to Westernport to confirm the existence of the bountiful lands which Hume and Hovell had described, and it was only then that Hovell realised that the two of them had in fact travelled to Corio Bay in Port Phillip, incorrectly marking it as Westernport. In fact, in our copy an annotation in pencil, most likely made at the Colonial Office, can be seen after the first page of the appendix on one of the blank leaves: ‘NB Port Philip is here confused with Western Port. See p.71’.

Though their mistake was publicised, corrections were not made to other navigational errors that had been marked on their original sketch maps, errors that were to be repeated in other major maps of the region that were created from their source material. Elements of details recorded in their journals have been misinterpreted and misquoted well into the 21st century and culminated in the Heritage Council of Victoria endorsing the heritage listing of an outlook on Monument Hill, Kilmore. In reality, the expedition only came as close as 1.4 kilometres to this viewpoint and even then, this was on the journey back.

A meticulous exploration of all the original source material, including the sketch maps was published in the Historical Journal of Victoria making the case that the heritage listing of the monument constructed on Monument Hill was made in error and that the historical record needed to be corrected, especially in the lead up to the bicentenary of this landmark journey to be celebrated in October, 2024. This expose was written by none other than Martin Williams, the historian who had reached out to us about our copy of the Journey of discovery to Port Phillip, New South Wales, by Messrs. W.H Hovell and Hamilton Hume, in 1824 and 1825.

Staff at the Foyle Special Collections library felt that this situation provided a fascinating opportunity to showcase the kinds of enquiries we receive, to highlight the impact that human error, confirmation bias and the spread of misinformation can have on the historical record, to emphasise the importance of the critical analysis of source material and to ultimately help publicise the 200 year anniversary of an event that shaped the development of a settlement that was to become modern day Melbourne, Australia.

***

The digitised copy of this item can be found online here on the King’s College London – JSTOR Open Community Collections page where you can view over 150 digitised items from 10 of our Archival and Special Collections.

If you would like to view this treasure in person or any other from our rich and storied collections then please contact us at specialcollections@kcl.ac.uk to book your visit today.

***

AEJ Andrews. Hume and Hovell, 1824. Blubber Head Press, 1981.

An extract from the Journal of Mr. Hamilton Hume, written on a tour through the interior to Bass’ Straits, in the Year 1824. (1831, July 4). The Sydney Herald (NSW: 1831 – 1842), pp. 3. [http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12843242] Accessed 16/09/24

Hume and Hovell. (1924, June 28). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW: 1842 – 1954), pp. 11. [http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16150184] Accessed 16/09/24

Hume and Hovell Expedition, 1824. Hume and Hovell Track. [https://www.humeandhovelltrack.com.au/hume-hovell-expedition] Accessed 16/09/24

In the paths of explorers (1946, October 2). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW: 1842 – 1954), pp. 10. [http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17997013] Accessed 16/09/24

M Williams ‘Hamilton Hume sketch maps: Origins and modern treatment’. Victorian Historical Journal, 92(1), pp. 5–31, 2021.

W Bland, WH Hovell & H Hume Journey of discovery to Port Phillip, New South Wales, by Messrs. W.H. Hovell and Hamilton Hume, in 1824 and 1825. A. Hill, printer. (1831).

State Library New South Wales. Captain William Hilton Hovell, explorer, July 1871 / photographer Oswald H. Allen. [https://archival.sl.nsw.gov.au/Details/archive/110344101] Accessed 16/09/24

State Library New South Wales. Hamilton Hume, explorer, ca. 1869 / photographer unknown. [https://archival.sl.nsw.gov.au/Details/archive/110344153] Accessed 16/09/24

State Library New South Wales. Hume and Hovell. [https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/stories/hume-and-hovell] Accessed 16/09/24