This blog is posted on behalf of Conal Priest, our 2020 MA History intern in the Foyle Special Collections Library.

My name is Conal Priest. I studied undergraduate History at the University of Exeter before moving on to a Masters course in Modern History at King’s College London, where I applied for an internship at the Foyle Special Collections Library at the beginning of my second term. I have been principally interested in a career in heritage since Sixth Form, though my interests narrowed towards curatorial work and collections management during my time as an undergraduate.

I have undertaken volunteer work at the University of Exeter Special Collections, interned at the Devon and Exeter Institution and the National Maritime Museum and helped to edit an undergraduate journal, The Historian. These were all diverse roles, ranging from work on book preservation and archival cataloguing, to extended academic research projects in significant archives. What I was missing, however, was direct experience of digitisation and the creation of exhibition materials; both of which I am attaining at the Foyle Special Collections Library.

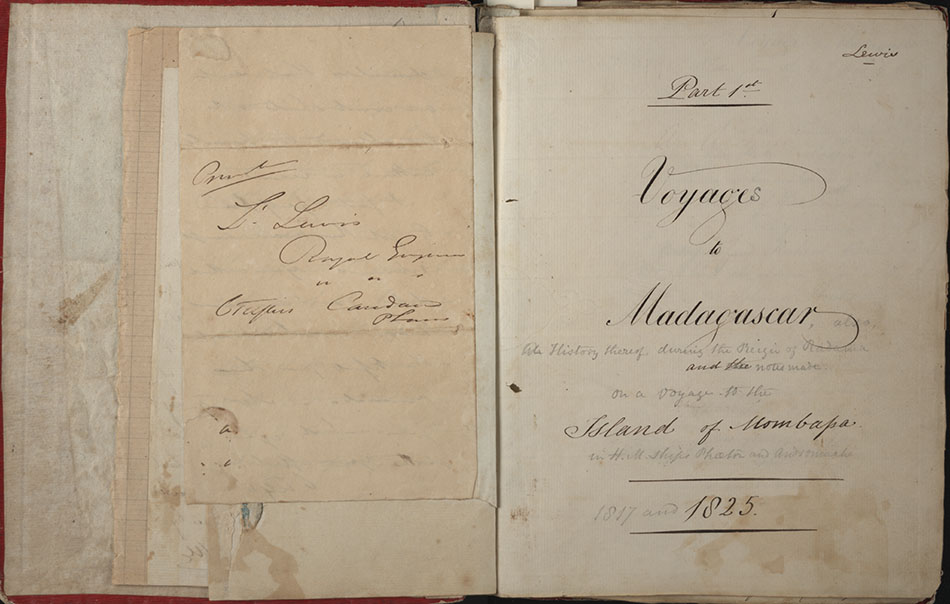

My project revolves around a manuscript entitled, Voyage to Madagascar: and the island of Mombassa, by Thomas Locke Lewis and which was written between 1817 and 1826. The manuscript was acquired by the collection from Maggs Bros Rare Books and Manuscripts, and complements the well-developed 19th century collection of manuscripts relating to British colonial interests. My initial task, and the one I am now coming to the end of is the transcription of the manuscript in preparation for the digitisation stage of the project.

I began the transcription with a solid foundation, having transcribed a substantial number of early 19th century letters, diary pages, and government reports as part of my undergraduate dissertation. However, the Locke Lewis manuscript posed its own challenges to overcome. Primarily, the marginal notes that are replete throughout the manuscript are often compressed and difficult to decipher, as are the amendments Locke Lewis appears to have made at some later date when he had access to reference books, such as those adding the genus names to the Malagasy plants he noted.

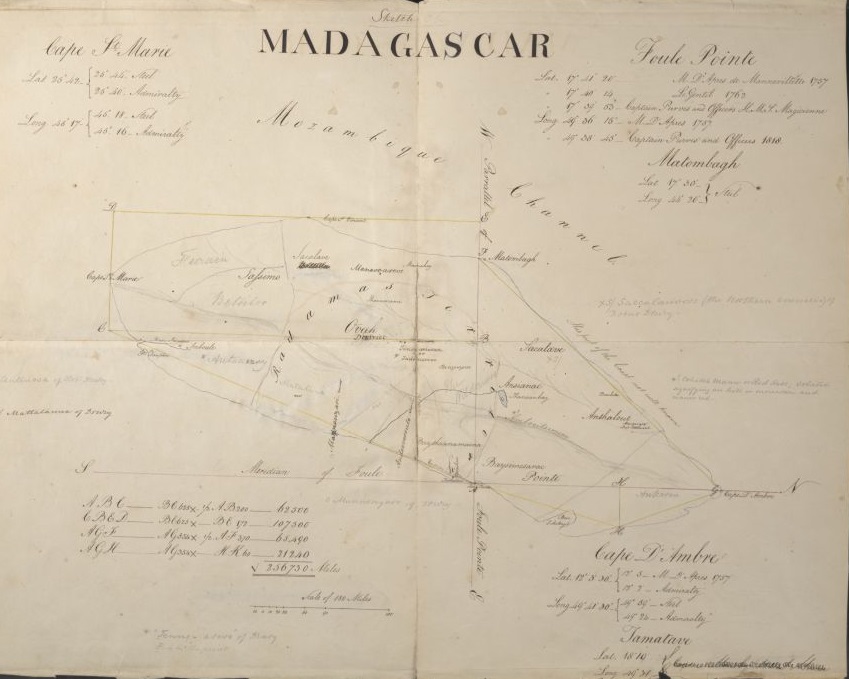

The sections, though difficult, have, like the rest of the manuscript, proved to be fascinating to transcribe. Locke Lewis’ writing sweeps from discussions of the geography and fauna and flora of the island that appear full of genuine scientific interest, towards more sober reflections on how these factors may be of interest to British trade and foreign policy.

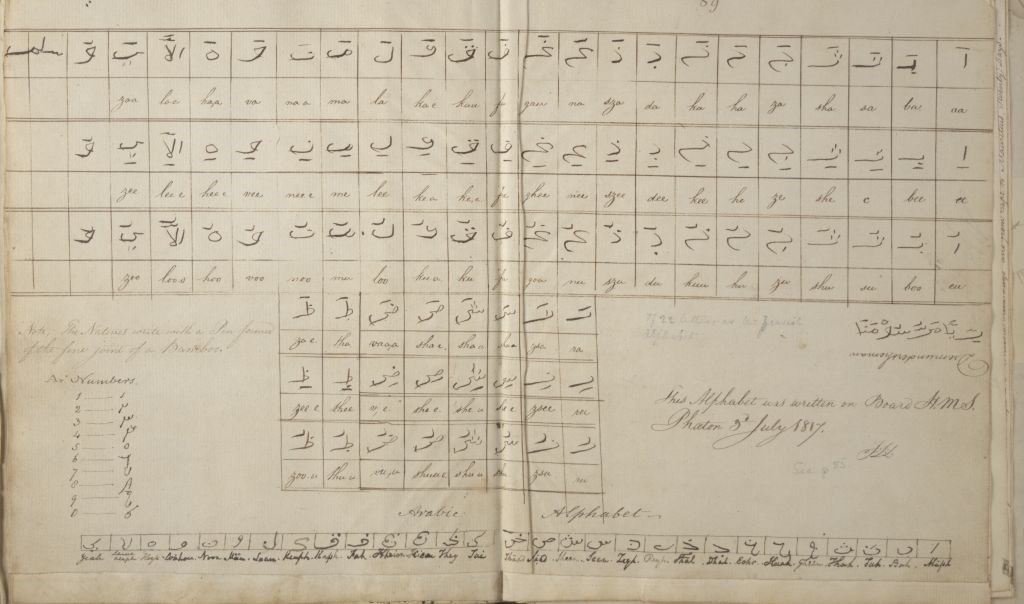

The language, culture, social structure, economics, religion, dress, ceremony, housing and tools of the Malagasy people are also discussed at length. Locke Lewis himself appears to have been interested in philology and produces many interesting reflections on what he theorised the antecedence of the Malagasy language may have been, and in a not unrelated way, how their social, cultural and religious practices related to their linguistic ancestors.

Once the transcription is finalised, I’ll move on to the digitisation phase of the project, working alongside Adam Ray, Special Collections Manager to produce a digital version of the book that can be accessed online by scholars and members of the public alike. The transcription and the digitisation will then form the basis of an online exhibition, which will contextualise the manuscript within the library’s collections, as well as alongside primary materials from the National Archives, and the historiographical discussions and debates that have taken places in relation to early 19th century Madagascar, British colonialism in the Indian Ocean, and the intellectual and practical pursuits of men of Locke Lewis’ station.

Being able to take a project from the very beginning, from transcription, through digitisation and onto a public-facing exhibition accessible to all is a very exciting opportunity. I am able to take the leading role in the project from the beginning; providing me with a new perspective on the life-cycle of such projects, their time-scales, and the individual skills involved in each part. I feel far more confident of how the stages leading to an exhibition, particularly one with a significant digital component, come together, and I look forward to implementing the skills I am learning in future curatorial work.