By Dr Manuela Pallotto Strickland, Metadata and Digital Preservation Coordinator

Writing to his father in July 1905, John Frederick Charles (Fritz) ‘Boney’ Fuller1 sorely lamented the miserable fate of those “poor freethinkers” who, like him, were “destined to eternal torment.”2 Whether Fuller was writing under the perduring spell of the mighty rhetoric of Doré’s Dante illustrations that had deeply impressed him as a child3, or was rather expressing a genuine sense of uneasiness and despair, no one can say for sure. Either way, the threat looming over Fuller’s fate (and allegedly the fate of all freethinkers a.k.a. sceptics a.k.a. agnostics a.k.a. heretics a.k.a. rational spiritualists a.k.a. enlightened occultists, magi etc etc), of an everlasting, inextinguishable, infernal torment had already been thought through and over, and finally debunked, by the 5-year version of himself, for such a torment, as Fuller had precociously decided as a child, could not really be “for ever and ever and ever, for then there would be no God.”4

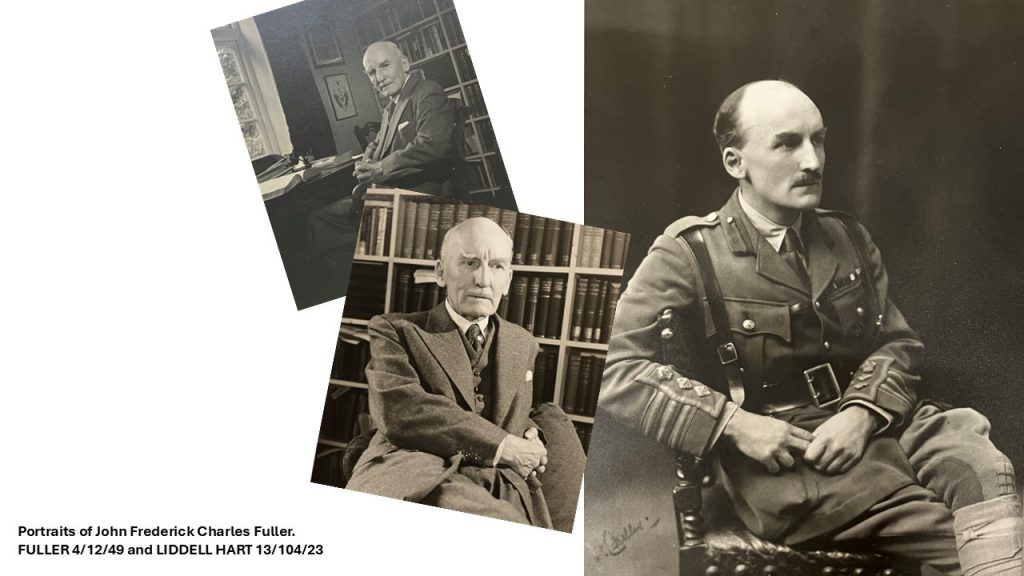

A proudly self-educated man, displaying, however, a noticeable penchant for comparing and questioning over and over the often unsatisfactory results of the various formal examinations he undertook, failed, and retook before and during his military career, Fuller has struck the imagination of both coeval and posthumous readers and biographers for the cultural and literary networks in which he moved throughout his life, milieus often perceived unseemly and troubling, particularly with regard to his life-long intellectual fascination with Occultism, Yoga, and Magic, and his active involvement in Mosley’s British Union of Fascists.5

Fuller was well aware of the ambiguous aura that enshrouded him; to a certain extent, not only did he not mind it but he also made efforts to validate it, by constructing a public image of himself as an iconoclast and an idiosyncratic persona, a freethinker who did not and could not fit in any of the existing, main-stream ‘systems’6– whether in the field of warfare theory and military studies, or more generally in that of politics and culture. Fuller’s dissent and unconventionality, rather than concealing a longing for social acceptance, stand as emblematic traits of his elitist view of the world and human history, which, under the influence of Kantian transcendentalism and Fichtian Idealism, combined Darwinist and Nietzschean vulgatae on the background of a syncretic, non-Christian, religious take on ancient Zoroastrianism and Gnosticism. A comprehensive early account of such a Weltanschauung is provided by Fuller in a remarkable letter to his grandfather, dated 19037, which we hold in our collections.

In the letter, a natural hierarchy distinguishing humankind in masters, disciples, and slaves is described and used to interpret modern phenomena in the realm of science, technology, and politics, and lays the basis for Fuller’s later critique of Western Democracy, of which a 1906 letter to his brother provides a very comprehensive overview. Fuller’s interpretation of European history in the pseudoDarwinian and Spenglerian terms of evolution and decay; his obsessive preoccupation with what today is called ‘Replacement Theory’, of which he left an uncannily early formulation in his analysis of the economic and demographic situation of the British Empire during those years; his scorn of socialism: all the topics that will characteristically populate his later writings are already present and articulated in the 1906 letter. The only ‘Fullerian’ topic missing in it is his antisemitism.

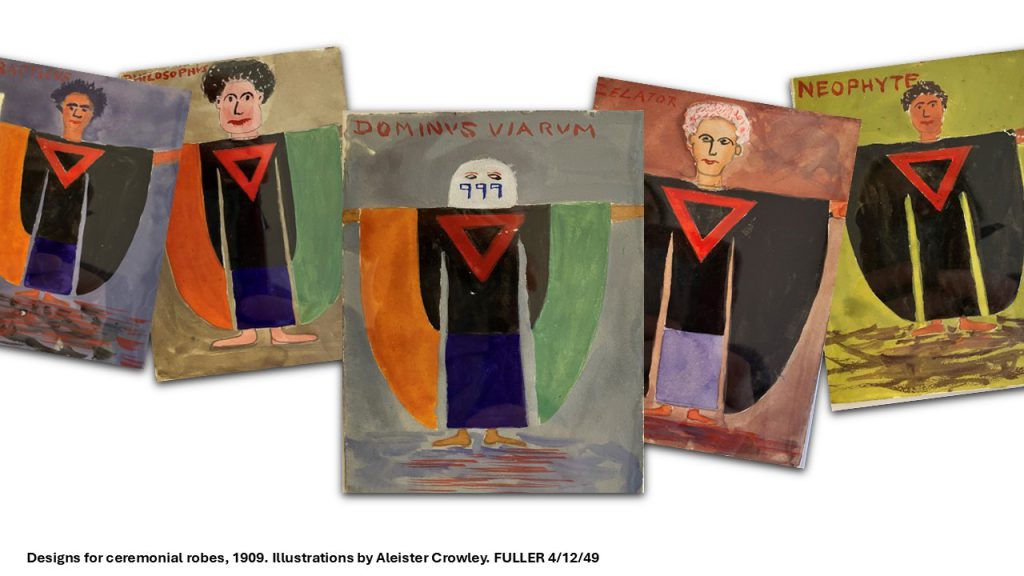

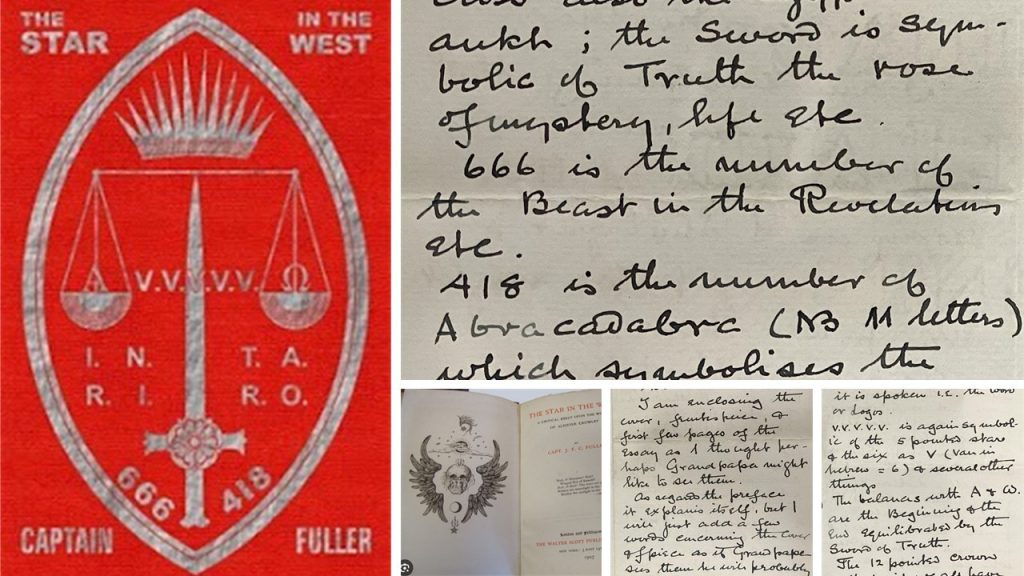

From the shared belief in the rights bestowed on great individuals by such a natural elitism, and the ensuing advocacy for an aristocratic approach to both secular and spiritual businesses, a creative relationship and an intimate friendship grew between Fuller and Aleister Crowley, who, just like Fuller, loved poetry and was convinced to be destined to great literary success. When Fuller met Crowley, upon returning to England from India where he had fallen seriously ill after contracting enteric fever, Crowley’s enfant terrible reputation was incipient in Rationalist and Agnostic circles – a reputation that Fuller likely found congenial. Keen to present Crowley’s work to the world (and possibly as eager to firmly establish himself as an author), Fuller wrote The Star in the West with the blessing and supervision of Crowley. Fuller not only wrote the essay; he also designed its cover and frontispiece, the symbolism of which he explained in a letter to his mother8. This extensive literary effort of Fuller in the field of Esotericism begot a creative collaboration, the development of which can be followed in the periodical The Equinox.

This intense relationship with Crowley has remained inconspicuously documented (if not altogether effaced) in Fuller’s military and political writings. The difference between the topics notwithstanding, the reader of Fuller’s texts on warfare, history, and political matters is never made aware of the writer’s interest and practices in the field of Occultism; nor it is ever revealed to them that the writer is the author of a rather large number of publications on related subjects.9 This seems particularly interesting when considering that, after breaking up with Crowley, Fuller kept publishing on esoteric and occult topics.10

In fact, as observed by Crowley, The Equinox had offered to Fuller the opportunity to refine his writing skills, which on more than one occasion Crowley, spitefully and rather ungratefully, described as mediocre. Without necessarily having to agree with the idea of a strong continuity between Fuller’s military and esoteric writings11, a certain consistency in the matter of Fuller’s style can be however recognised, regardless of what he was writing about. Similarities in the overall tone and, often, vocabulary, as well as an evident predilection for triadic reasoning, punctuate his books and articles on the theory of warfare. His peculiar propension to jump on any available opportunity and draw yet another sophisticated diagram, is also plainly manifest in his military works, with Fuller not always being able to conceal any apparent resemblance to the geometric illustrations he had produced for Crowley (which Crowley highly praised).

Fuller’s skills as an illustrator are seldom highlighted; and yet, during the Equinox years, his contributions to the periodical were equally visual and textual. Despite lamenting Fuller’s skills in representing the human figure, and despite the resentful claim that he could easily replace Fuller’s artistry, after their breakup Crowley did not seem able to find anyone suitable who could illustrate his periodical in Fuller’s stead. As a consequence, in 1913 and 1914, issues of The Equinox do not include figurative illustrations; when looking at Crowley’s own drawings, we are grateful for the original, underpinning editorial decision …

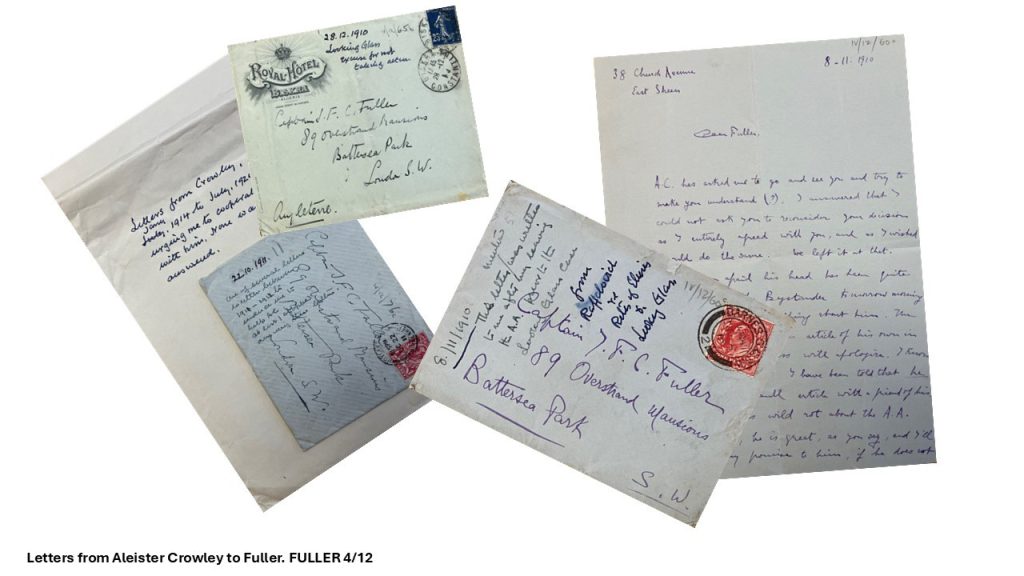

The relationship between Fuller and Crowley, which has been very recently thoroughly investigated and reconstructed12, came to an end within the space of six years, when Fuller executed a most decisive act of severance, aiming to dispose of any ambiguity left about his utter estrangement from Crowley and his entourage. With the deliberate gesture of someone who is leaving evidence to posterity, Fuller annotated the envelopes which contained the letters Crowley wrote to him during those critical months, to provide his own interpretation of those documents. He also conserved a copy of one of his letters to Crowley (possibly the only letter written by Fuller to Crowley that has reached us), in which his decision to interrupt their relationship is clarified and presented as most definitive13. The colourful account of the whole ordeal provided by Crowley in his autobiography14 substantially confirms Fuller’s narrative.

The breakdown of their friendship happened rather suddenly and was occasioned by the notorious Looking Glass libel (1911), specifically by Crowley’s decision not to protect his own reputation and that of his circle by suing The Looking Glass newspaper. One cannot but wonder whether Fuller would have sought for a different excuse to cut all ties with Crowley, had Crowley decided to sue The Looking Glass like the majority of his friends was asking him to do – or, rather, would he have maintained an active involvement in Crowley’s poetic and literary endeavours, to which, at that point, he had been consistently contributing for over five years, and spent no time at all considering a military career.

In 1962, the War Studies Department of King’s College London was founded by Sir Michael Howard, lecturer in Military Studies and one of England’s foremost military historians. Two years later, Howard established a Centre for Military Archives at King’s to complement the new department. The Centre’s remit was simple: it would collect the papers of senior defence personnel of the twentieth century. The official launch of this archive was timed for 1964, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War. In 1973, the archive was renamed the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives in honour of Sir Basil Liddell Hart, whose own extraordinary collection of over 1000 boxes of papers is still the single largest, and one of the most often used, in the LHCMA.

2024 thus marks the LHCMA’s 60th anniversary. In those intervening years we have gathered the personal papers of over 800 senior defence personnel, and we thought this birthday year was a great opportunity to showcase just some of the items from the collection. Every month this year we will be publishing a blog post spotlighting one item or collection chosen by a member of staff. We hope you enjoy celebrating with us!

You can read last month’s post about the immediate lead-up to the Second World War by clicking here.

- The story goes that Fuller gained his nickname because of his admiration of Napoleon I. See the two main biographies: Trythall, A. J. (1977). “Boney” Fuller: the intellectual general, 1878-1966. Cassell; and Reid, B. H. (1987). J. F. C. Fuller: military thinker. Basingstoke: Macmillan. ↩︎

- Letter from Fuller to his father, 20 July 1905. FULLER 4/3/115-139b. ↩︎

- “Men and women frozen in the mud, blazing in hell fire, turned into gnarled trees and into crawling spiders.” Fuller, J. F. C. (1936). Memoirs of an Unconventional Soldier. London: Ivor Nicholson and Watson, p.2. KCL Special Collections’ copy (from the library of Major-General J.F.C. Fuller (1878-1966)) contains ms. inscription and signature in green ink on first free endpaper: “To Colonel and Mrs. Hutton with the best wishes of J.F.C Fuller, 3/7/1936”. King’s College bookplate on front pastedown indicates item was the gift of Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Hutton. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- On Fuller’s fascism, his role in defining Mosley’s party upon his becoming a BU member in 1935, and his relationship with other Fascism representatives and advocates, see, besides Trythall (1977) and Reid (1987): Zook, D. H. (1959). John Frederick Charles Fuller Military Historian. Military Affairs, 23(4), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.2307/1984602; Reid, B. H. (1998). Studies in British military thought: debates with Fuller and Liddell Hart. University of Nebraska Press; Simpson, A. W. B. (1992). In the highest degree odious detention without trial in wartime Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press; Thurlow, R. (1987). Fascism in Britain: a history, 1918-1985. Oxford: Basil Blackwell; Renton, D. (1999). The attempted revival of British fascism: fascism and anti-fascism, 1945-51. PhD thesis, Department of History at the University of Sheffield; Linehan, T. P. (2000). British Fascism, 1918-1939: parties, ideology and culture. Manchester: Manchester University Press. https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526162205; Watson, Mason W. (2012). “Not Italian or German, but British in Character”: J. F. C. Fuller and the Fascist Movement in Britain. Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 485. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/485; Holmes, C. (2016). Searching for Lord Haw-Haw: The Political Lives of William Joyce. Routledge; Imy, K. (2016). Fascist Yogis: Martial Bodies and Imperial Impotence. Journal of British Studies, 55(2), 320–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/jbr.2016.1. Although focused on Crowley, see also Pasi, M. (2014). Aleister Crowley and the Temptation of Politics. London: Routledge. ↩︎

- “I cannot fit into systems […], systems have to fit into me.” Fuller to Meredith Starr, 3 August 1933; quoted in Reid (1998), p.183. ↩︎

- FULLER 4/3/115a. ↩︎

- FULLER 4/3/139c. ↩︎

- Although, it would not escape the attention of the reader familiar with Crowley’s work that the closing of Fuller’s autobiography is an (unreferenced) quotes from Crowley: “Fear is failure, and the forerunner of failure. Be thou therefore without fear; for in the heart of the coward virtue abideth not.” See The Master Therion (aka, Crowley, A.) (1917). The Revival of Magick. The International, 9(8), pp. 247-248. ↩︎

- In 1925, Fuller authored Yoga: A Study of the Mystical Philosophy of the Brahmins and Buddhists (London: W. Rider, 1925); in 1926, Atlantis. America and the future (London: Kegan, Trench & Tubner); in 1937, The Secret Wisdom of the Qabalah: A Study in Jewish Mystical Thought (London: W. Rider & Co., 1937). He also published several articles in the Occult Review periodical: A Study of Mystical Relativity (1933, May to July); Magic and War (1942, April); The Attack of Magic (1942, October); The City and the Bomb (1944, January). ↩︎

- Kaczynski, R. (2024). Friendship in doubt: Aleister Crowley, J.F.C. Fuller, Victor B. Neuburg, and British agnosticism. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197694008.001.0001. ↩︎

- Kaczynski 2024. ↩︎

- See items of correspondence in FULLER 4/12. ↩︎

- Crowley, A., Symonds, J., & Grant, K. (1989). The confessions of Aleister Crowley: an autobiography. Arkana. ↩︎