By Lavinia Griffiths, Foyle Special Collections Library, King’s College London

Outstanding among the treasures of the Foyle Special Collections Library are its holdings of rare books: some 12,000 printed items, from a 1483 edition of the Punica of Silius Italicus to first editions of the novels of Charles Dickens and the Left Book Club’s 1937 edition of George Orwell’s The road to Wigan Pier, with pre-1850 imprints at its core. They cover a wide-range of subjects from history and literature to music and sciences. Particular strengths are theology, Byzantine and Ottoman studies, and travels and voyages of exploration. An easily overlooked item – it came to our attention through our participation in the Book Owners Online project (BOO) is the object of the present note.

Led by David Pearson and hosted by UCL, BOO aims to create an online database of English book owners active between 1630 and 1710. Short Wikipedia-style entries (so far just over 2,000) provide a valuable reference work not only for book history and but also for the intellectual history of the period. Running the names of 17th century owners in our catalogue against the BOO set produced 13 matches, as well as links to family members of a further three. There were, in addition, four owners on our system for whom BOO has as yet no entry. One of them is John Trotter (1667-1718), of Mortonhall, Edinburgh, a former owner of the book discussed below.

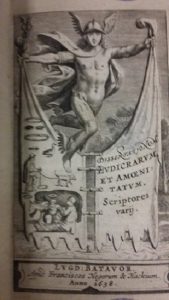

This small leather-bound book (13 x 8 cm): Dissertationum ludicrarum et amoenitatum (Playful discourses and delights) is the work of various authors (Scriptores varii) and was published in Leiden in 1638 by the printers Franciscus Hegerum and Franciscus Hackium.

This small leather-bound book (13 x 8 cm): Dissertationum ludicrarum et amoenitatum (Playful discourses and delights) is the work of various authors (Scriptores varii) and was published in Leiden in 1638 by the printers Franciscus Hegerum and Franciscus Hackium.

The duodecimo volume (one where each printed sheet has been folded three times to create gatherings of 12 leaves), with its engraved title page featuring Mercury (a popular device for ‘news’ and wit) contains a collection of Latin compositions with such titles as ‘In praise of the goose’, ‘An encomium on the flea’, ‘In praise of gout’ (Laus anseris, Encomium pulicis, Laus podagrae).

It belongs to a Humanist genre of rhetorical exercises comprising witty paradoxes and squibs. That a second edition was published in 1644 suggests it was well received. The Heritage of the Printed Book database provides details of 19 copies in North American and European libraries, of which nine are of the 1638 edition.

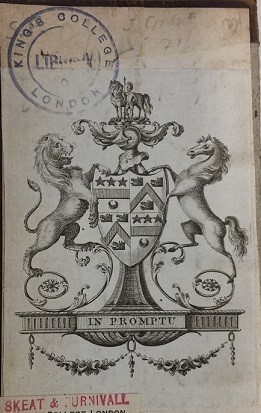

Our copy is of especial interest because it contains multiple marks of provenance. The library stamp in the top left corner of this bookplate, affixed to the front pastedown, indicates that the book is the property of King’s College London’s library. The stamp in red at the bottom of the bookplate refers to two English scholars, Walter William Skeat (1835-1912), Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Cambridge, and Frederick James Furnivall (1825-1910), who worked together in the Early English Text Society, and whose libraries were presented to the Department of English at King’s in 1911 and 1913, respectively.

Our copy is of especial interest because it contains multiple marks of provenance. The library stamp in the top left corner of this bookplate, affixed to the front pastedown, indicates that the book is the property of King’s College London’s library. The stamp in red at the bottom of the bookplate refers to two English scholars, Walter William Skeat (1835-1912), Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Cambridge, and Frederick James Furnivall (1825-1910), who worked together in the Early English Text Society, and whose libraries were presented to the Department of English at King’s in 1911 and 1913, respectively.

How the book came into their hands remains a mystery. The bookplate itself dates to the early 18th century and bears the arms of the Trotter family of Mortonhall, near Edinburgh. That library, comprising over 1,000 titles (mostly works on grammar, logic, lexicography, and religious controversy, with some rare medical books), was kept more or less intact until it was sold in 1947 when most of the books seem to have passed into private hands. Further research might reveal whether one or both of the philologists had a connection with Mortonhall.

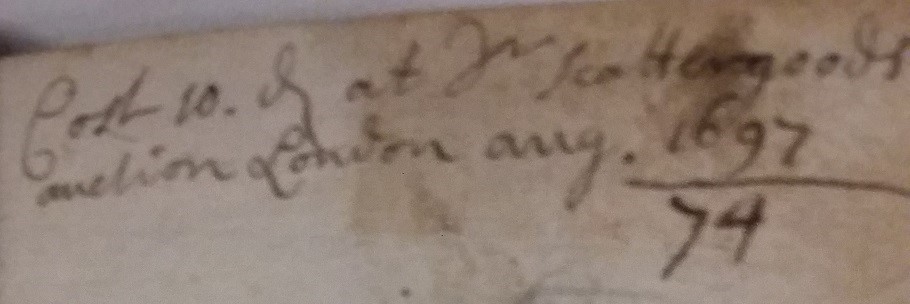

Opposite the bookplate, on the first free endpaper there is an ink inscription:

It is written in the distinctive hand of John Trotter (1667-1718), the son of John Trotter, first Baron of Mortonhall, an Edinburgh merchant who had bought the estate in the middle of the 17th century. The younger John Trotter was to become a keen book collector, frequenting auctions from an early age. One of his practices was to annotate his acquisitions with details of where he had bought them and the price paid. One such record is in a dictionary which he had purchased for ‘£3 10 s., Scotch’ at an auction held on 4 February 1795, noting his chagrin at having only obtained the first part and his efforts to acquire the second: ‘I heard that Dr Sibald had ye last pt but he wants this & yet I could not prevail wt him to pt wt it or to throw the dice wt me who should have both.'[see the reference to MA Bera in Further Reading, below].

The auction referred to in our inscription is that of the library of Anthony Scattergood (1611-87), prebendary of Lincoln and Lichfield and a celebrated writer of sermons and biblical scholar. Educated at Trinity College Cambridge, he served as chaplain and librarian to John Williams (1582-1650), the bishop of Lincoln, and future archbishop of York, who was himself an important library benefactor. Anthony bequeathed his own library to his son, Samuel Scattergood (1646-96). He, too, had attended at Trinity, where Isaac Newton was a contemporary, before succeeding to his father’s prebends.

After Samuel’s death the library was auctioned by John Hartley, a bookseller established near Gray’s Inn in Holborn, on 26 July, 1697. The collection was considered of sufficient importance to warrant a printed catalogue: A catalogue of the library of the reverend and learned Dr. Scattergood, deceas’d containing a curious collection of Greek and Latin fathers, councils, historians, philosophers, poets, orators, lexicographers, &c. : also an excellent collection of English, French, Italian, and Spanish books in all faculties (Wing S840).

Copies were widely circulated: Catalogues may be had gratis at Mr. Hinchman’s in Westminster hall, Mr. George Huddleston’s at the Black-Moor’s-head in the Strand, Mr. Brown’s without Temple-Bar, Mr. Wellington’s at the Lute in S. Paul’s Church yard, Mr. Bell’s at the Cross-keys in Cornhil, Mr. Clement’s in Oxford, and at the place of sale.

The catalogue provides a fascinating insight into the contents of a 17th century cleric’s library. As might be expected, there is much history, philosophy, theology, and natural history, but there is also some literature, including poems by Spenser and Milton, and, intriguingly, ‘betwixt Fourscore and an Hundred “Italian” Plays’.

The article for Anthony Scattergood in Book Owners Online had noted that none of the books in the catalogue had been identified, but we have been able to report that our copy is certainly the title listed as lot 128 in the section Libri Miscellani in Duodecimo, etc. We have also contributed a new entry for John Trotter in BOO.

The article for Anthony Scattergood in Book Owners Online had noted that none of the books in the catalogue had been identified, but we have been able to report that our copy is certainly the title listed as lot 128 in the section Libri Miscellani in Duodecimo, etc. We have also contributed a new entry for John Trotter in BOO.

Thus, with some help from BOO, an examination of provenance marks has enabled us to trace the journey of this little book over the course of nearly four centuries, from its printing in Leiden, to the library of the prebends of Lincoln and Lichfield, to the Holborn bookseller, and to the Edinburgh book collector, before it came to King’s as part of the Skeat and Furnivall Collection.

Further reading

Please note that we have included in this article some links to resources subscribed to by King’s College London Libraries & Collections.

MA Bera, ‘Remarques upon the French Language by John Trotter, Gentleman’, The Modern Language Review; Cambridge Vol 45, (Jan 1, 1950): 518

City of Edinburgh Council, Edinburgh. Survey of Gardens and Designed Landscapes. 214 Mortonhall

JF Fulton, The great medical bibliographers: a study in humanism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1951

Princeton University Library, Special Collections blog. ‘Trotter family library copy: armorial bookplate with motto: In promptu’

H Quehen, ‘Scattergood, Anthony (bap 1611, d 1687), Church of England clergyman’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, retrieved 10 Nov 2021