This post is written by Hannah Parry, MA Contemporary British History

This term, I have had the privilege of taking up an internship at the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives – within the King’s College London Archives – as part of my MA in Contemporary British History.

The focus of my internship has been the life of Kitty Wintringham (1908-1966), and I have spent the Spring term putting together an online exhibition on her life and legacy.

Caption: Kitty Wintringham. Wintringham 11/4, LHCMA.

Kitty was the wife of Thomas Wintringham (1898-1949), whose extensive papers the Centre holds. Tom was the leader of the British battalion of the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War (1936-9), as well as a prolific writer and political activist. He established the Home Guard training school in Britain during the Second World War and was a founding member of the socialist Common Wealth Party in 1941.

Kitty immediately struck me as a fascinating woman. She was born in Colorado in 1908 and grew up in a wealthy and conservative family in New York. She attended Bryn Mawr women’s college, where she studied politics and economics, but after graduating she became disillusioned with life ‘in the upper brackets of society.’ Having studied politics and economics, she was fascinated by socialism and economic policy, and set off to visit the Soviet Union aged 28 in 1936, in her words ‘for some perspective.’

After a short stint in Paris, she eventually made her way to Spain, where civil war had broken out, and where so many of her generation had flocked to join the Republican socialist cause. There, she met Tom Wintringham, apparently in a café on a warm September evening in Barcelona.

Caption: Tom and Kitty. Wintringham 11/4, LHCMA.

Kitty’s relationship with Tom underlines the central paradox of her life contained within the collection. Kitty’s independent mind and irreverent wit spill out of her papers, and yet so much of her life and work was determined by her husband’s political career. Kitty worked as a journalist for the Manchester Guardian whilst in Spain, and after the couple arrived in London in 1938, she wrote for the Federated Press of New York about British politics and the international tensions which were brewing across Europe.

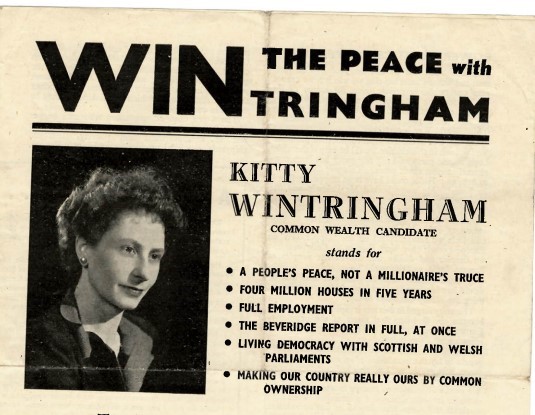

During the Second World War, Kitty worked with Tom to publish the numerous articles, pamphlets and books on military strategy which he penned. Although he described her work as ‘secretarial’, she spent long hours typing up his manuscripts and contributing ideas; and it was during this period when Tom gained such political prominence. Kitty stood as a Common Wealth candidate in the 1945 General Election, but lost badly to her Labour rival.

Caption: Kitty’s campaign literature from 1945. Wintringham 3/2/5 LHCMA.

Kitty’s papers come to an abrupt end with Tom’s death in 1949, and the final file contains the numerous letters of condolence she received when he died suddenly of an aneurysm. Her papers sit as a small but significant sub-section of his collection, and one is left wondering how many other stories of women’s lives are subsumed and obscured by those of their male counterparts.

Studying this collection has been hugely enriching in the perspective it offers on the women of Kitty’s generation; and Kitty’s letters, reflections and articles make for fascinating reading.

Kitty committed suicide in 1966, and the view of Tom’s biographer, Hugh Purcell, is that after Tom had died and their son had left home, she had nothing left to live for. Such a complex and sensitive matter is of course impossible to resolve; but Purcell’s dismissive attitude towards Kitty belies the independence, audacity and courage she showed throughout her life.

Whilst Kitty has been remembered as an appendage to Tom’s political legacy, my aim in putting together this online exhibition has been to shed light on the complexities of her life and work, and the ways in which she both deferred to and defied the expectations of her era.

Online Exhibition:

A glance at the life of Kitty Wintringham, journalist, campaigner and political activist, 1908-1966. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/f33ed74664c14cd29a4fd0ce619b7bfb