By Toslima Khatun, Post-Doctoral Researcher, King’s College London Archives

General Edmund Ironside (d.1959) was a prominent member of the British Army, and instrumental in the fight against the Bolsheviks in Northern Russia (particularly in Archangel) right up until the whole country was lost by Western European efforts against communism and anti-monarchism. Ironside, who was firmly on the sides of the ‘whites’ and led the British efforts, wrote a prolific series of diaries/accounts of his day-to-day life in Russia and everything he considered of note.

The diaries are all handwritten by (we presume) Ironside himself, given the personal remarks and deductions he makes of people he has met. This included value judgments of those he did not surmise to meet their fullest potential. In parts his writings are both witty and scathing, and yet surprisingly compassionate.

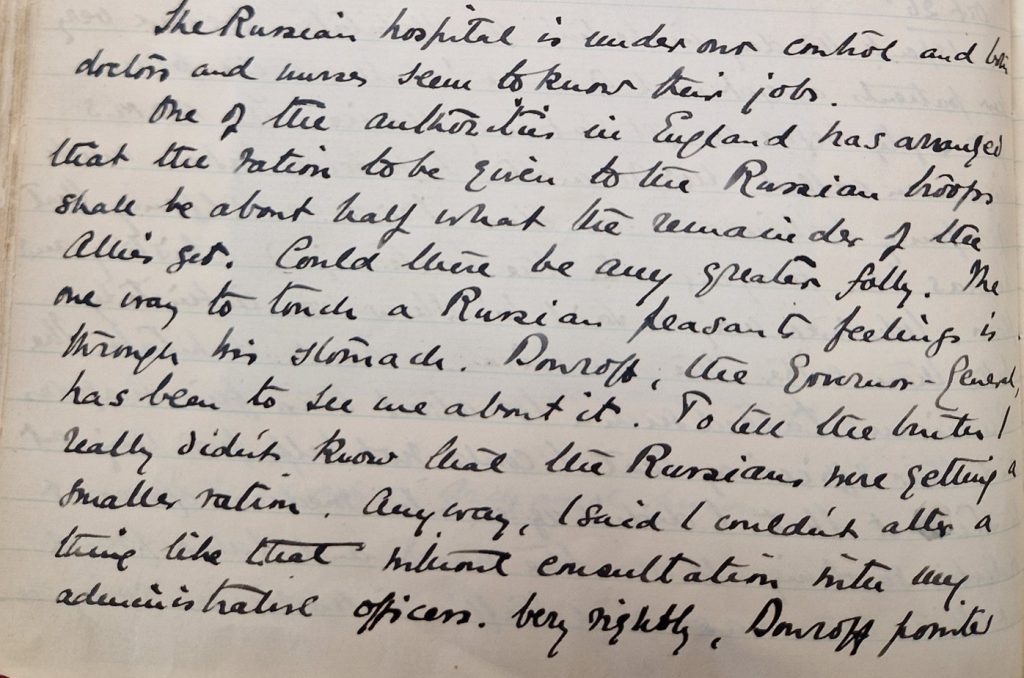

He recounts visiting each hospital within the territories he controlled and his observations in each. The hospitals were divided by nationality to provide provisions in line with the soldiers’ needs. Surprisingly, once witnessing the conditions of the Russian hospital and the lack of equipment, Ironside is appalled. He specifically takes time out of his military and governance schedule to speak to the head doctor and upbraid him about the conditions the Russian men were in.

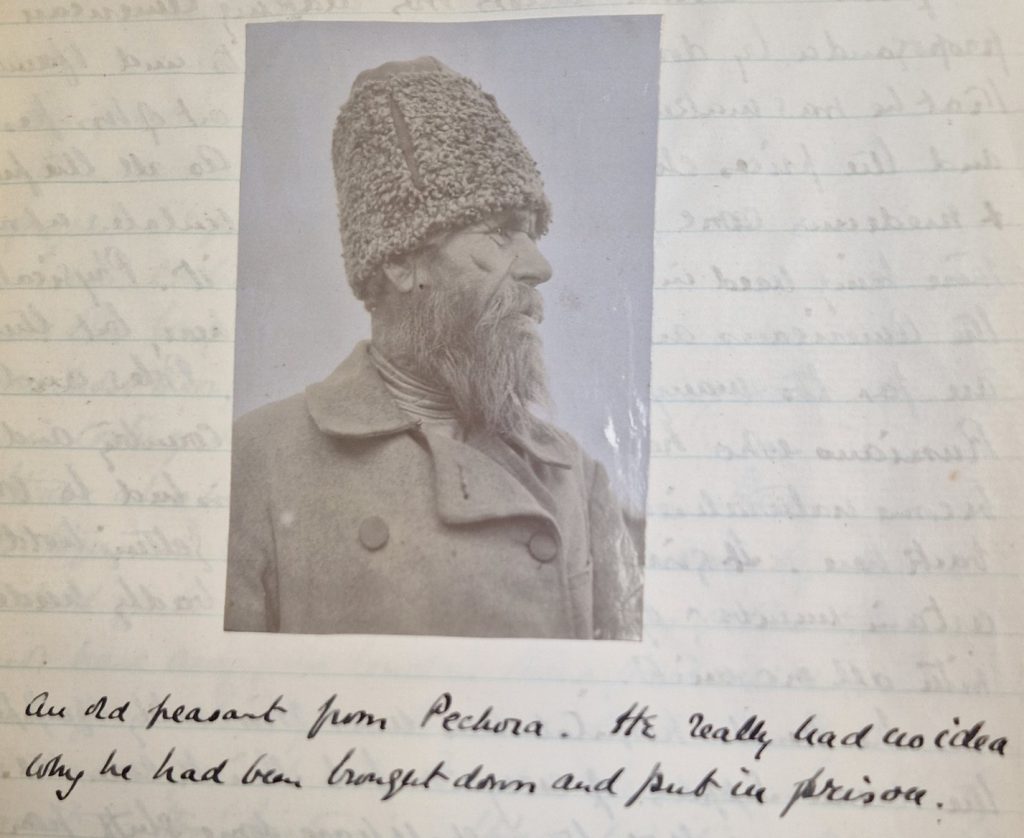

Ironside’s empathy towards those under his responsibility is apparent as a theme throughout the diaries, and this is not the only example. There are pictures he takes of ‘peasants’ that are arrested in newly acquired territories that he freely admits have no idea what is happening. He recounts making sure they are fed, and rationalising that they were apart from the governments that were vying for control over them.

The humanness of such an account, and the honesty it involves (whether it is polished or retrospective) is a novel approach to war accounts that does stand this series of diaries apart. His diaries were written at the latest during the height of the Cold War, and there was no incentive to try and humanise what were considered ‘the other’. This makes the diaries even more interesting and worth studying.

If you want to learn more about the Ironside diaries, then come along to our event celebrating the acquisition of the collection on Tuesday 12th March! Tickets are free – read more and book here.

In 1962, the War Studies Department of King’s College London was founded by Sir Michael Howard, lecturer in Military Studies and one of England’s foremost military historians. Two years later, Howard established a Centre for Military Archives at King’s to complement the new department. The Centre’s remit was simple: it would collect the papers of senior defence personnel of the twentieth century. The official launch of this archive was timed for 1964, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War. In 1973, the archive was renamed the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives in honour of Sir Basil Liddell Hart, whose own extraordinary collection of over 1000 boxes of papers is still the single largest, and one of the most often used, in the LHCMA.

2024 thus marks the LHCMA’s 60th anniversary. In those intervening years we have gathered the personal papers of over 800 senior defence personnel, and we thought this birthday year was a great opportunity to showcase just some of the items from the collection. Every month this year we will be publishing a blog post spotlighting one item or collection chosen by a member of staff. We hope you enjoy celebrating with us!

You can read last month’s post about poetry in the trenches by clicking here.