By Oliver Snaith, Archives Assistant, King’s College London Archives

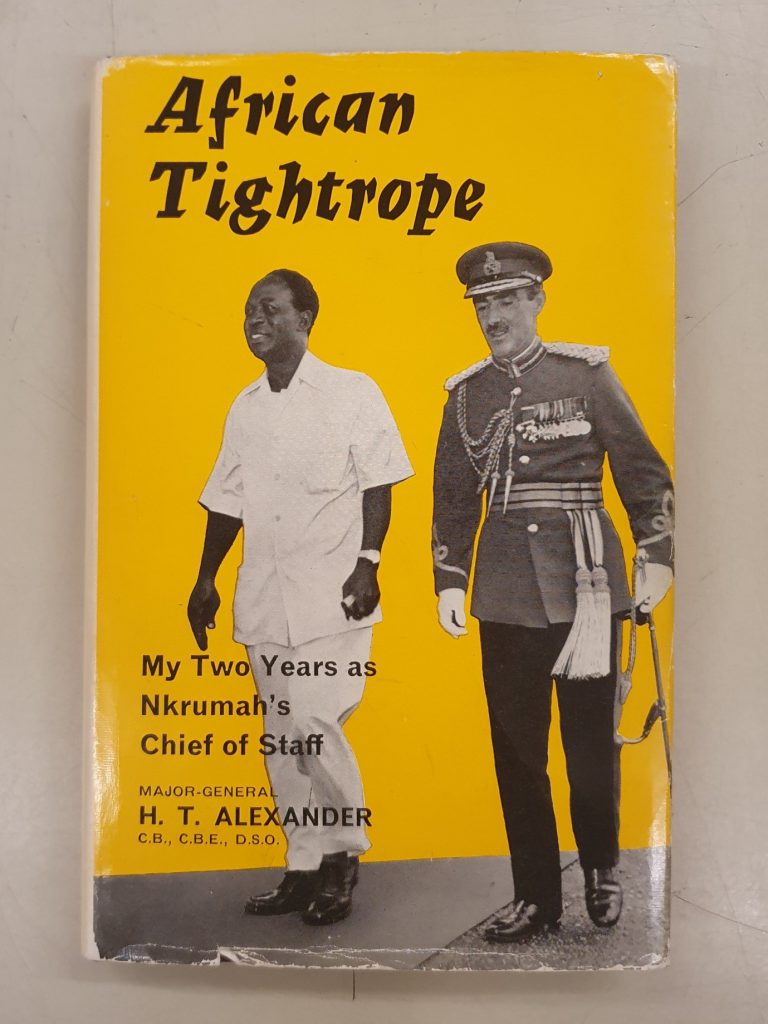

The Archive of Major-General Henry Templer Alexander (1911-1977), which consists of one box of original material and a copy of his published memoir African Tightrope: My Two Years as Nkrumah’s Chief of Staff, provides insights into the functioning of African states in the years immediately after they gained independence, and into how Cold War rivalries played out in Africa as newly independent states established their own foreign policies while the great powers fought for influence.

Alexander became Chief of Staff in Ghana on 5 January 1960, almost three years after Ghana became independent from Britain, having had no previous experience in Africa. The appointment of a British officer as Chief of Staff after independence reflected the common tendency for newly independent African states to continue to rely on senior military personnel from their former colonial power. The replacement of British officers with Ghanaians, known as Ghanaianisation, was a contentious issue throughout Alexander’s time as Chief of Staff, and was demanded by President Kwame Nkrumah and many other Ghanaians. During his time in Ghana, Alexander developed plans for rapid Ghanaianisation at Nkrumah’s request. The Ghana Armed Services also faced the issues of expansion and the purchase of new equipment. Nkrumah was a supporter of Pan-Africanism who sought to build economic and political union between African states and non-alignment in the Cold War, and wished not only to Ghanaianise the officer corps but also to expand the armed forces, wishing, according to Alexander, to purchase new equipment without considering costs (African Tightrope, 98-99). During Alexander’s time as Chief of Staff, Nkrumah remained committed to non-alignment, but from 1961 he sought military assistance from the Soviet Union.

Alexander displayed complex attitudes towards Ghana. He was frequently dismissive of Ghanaian capabilities, believing that independence had resulted in a ‘sudden drop in administrative efficiency’ (African Tightrope, 111), condemning the rapid granting of independence to African countries without adequate preparations (African Tightrope, 123), and being suspicious of Nkrumah’s Pan-Africanism. He was also keen for Western influence in Africa to be maintained, saying in the postscript of African Tightrope that if the West did not succeed in retaining influence ‘we will lose our trade and our contacts with African countries’, which would result in NATO being ‘outflanked’ and becoming ‘meaningless’ (African Tightrope, 126). However, he accepted African independence as inevitable, and believed that attempts by colonial powers to prevent independence would increase the appeal of Pan-Africanism and Communism (African Tightrope, 126). He always claimed to want what was best for the people of Ghana, and always couched his proposals for the Ghana Army and his objection to Nkrumah’s attempts to pursue rapid expansion and seek Soviet assistance in terms of military effectiveness. Despite distrusting Nkrumah’s Pan-Africanism and trying to influence his defence policy, Alexander always professed loyalty to him, arguing that his favoured courses of action would benefit him and Ghana in the long run. Despite his evident desire for Ghana to avoid Soviet assistance, his belief that it and rapid expansion of the Armed Services at the same time as Africanisation would harm the Armed Services was most likely genuine, as he wrote in African Tightrope that ‘consistency and honesty in one’s recommendations to him were surely the best’ (African Tightrope, 108).

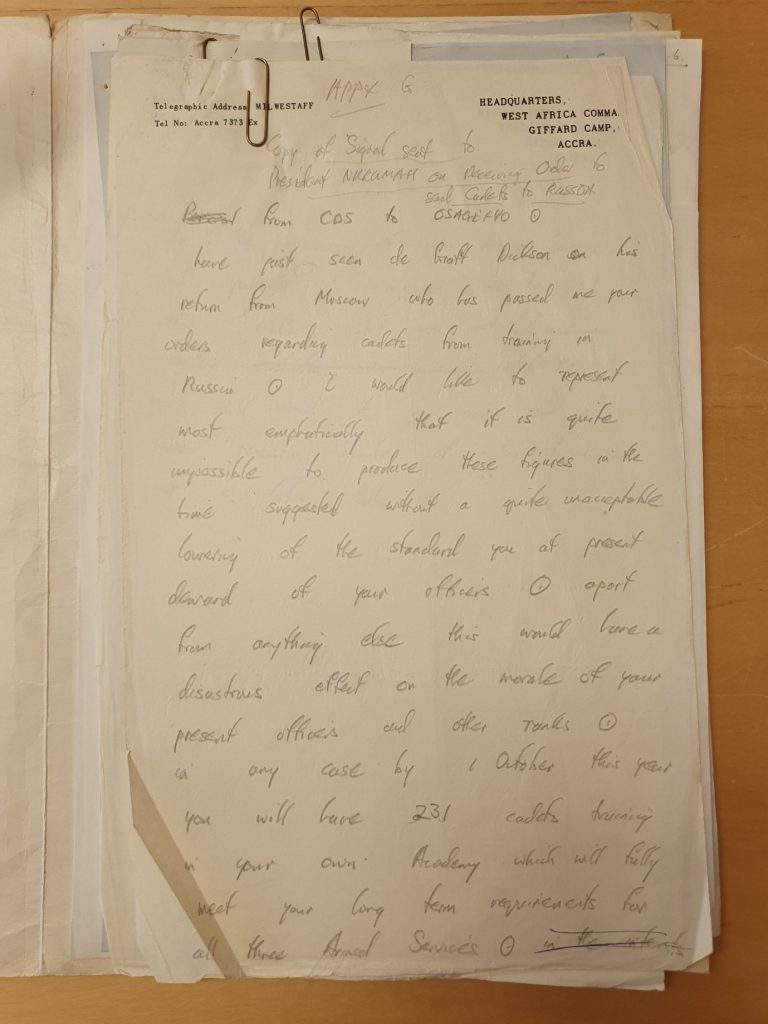

The way Alexander made his case can be seen in the sequence of events which ended with Alexander’s dismissal in September 1961. Nkrumah went on a tour of the Eastern Bloc, and shortly afterward a plan to train 400 cadets in Moscow was announced. Alexander strongly warned Nkrumah against this plan and argued that it would degrade the effectiveness of the armed forces (Figure 2), stating that ‘it is quite impossible to produce these figures [i.e. the number of officers the Soviets were planning to train] in the time suggested without a quite unacceptable lowering of the standard you at present demand of your officers…apart from anything else this would have a disastrous effect on the morale of your present officers and other ranks’.

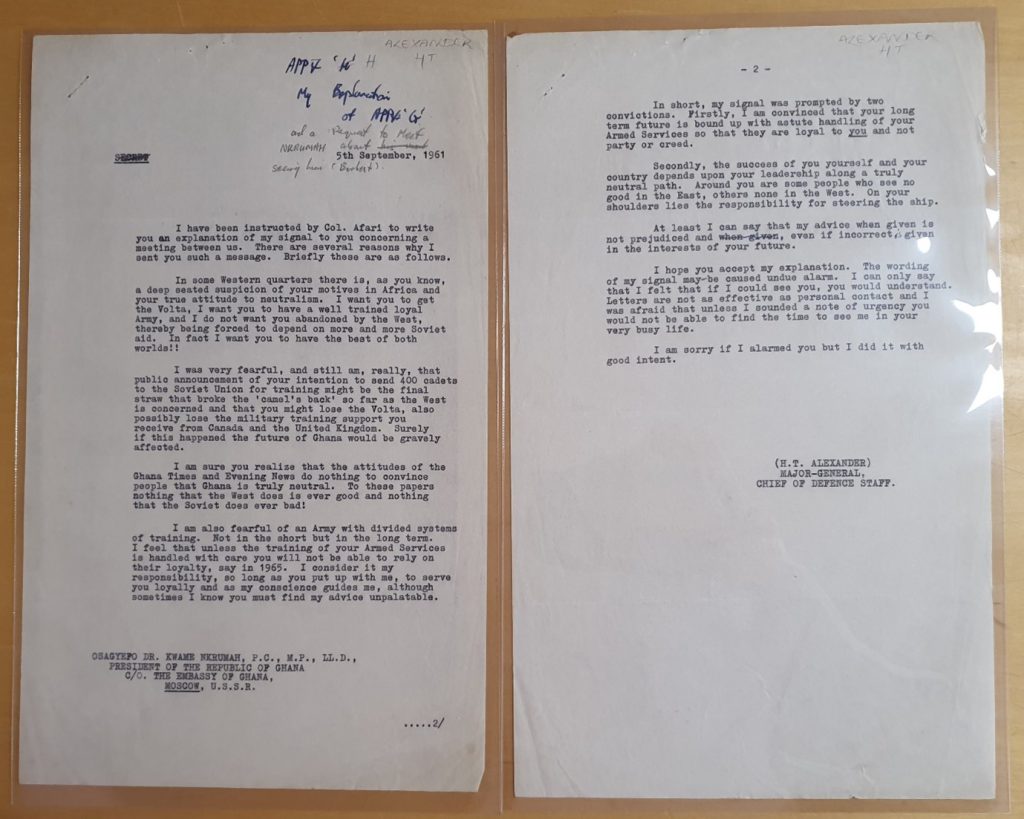

Alexander was concerned about the plan to send cadets to Moscow not only because of the risk it posed to military effectiveness but also because of a desire to retain British influence in Ghana, as indicated by the fact that, in a report written after his dismissal, he noted that Nkrumah had turned rapidly against the British, motivated by British actions during the Congo crisis, and advocated a visit by a member of the British cabinet to Ghana to prevent relations from deteriorating further. Alexander made his concern about the international consequences of Ghana’s decision clear in a message to Nkrumah dated 5 September 1961 (Figure 3), in which he stated that ‘In some Western quarters there is, as you know, a deep seated suspicion of your motives in Africa’. He warned Nkrumah that sending cadets to Moscow would cause Ghana to lose the aid that it was receiving from Britain. However, this message was not couched purely as a warning about the dangers of breaking with the West, but also as a warning about military effectiveness, since Alexander warned of the consequences of having an army with divided training. He also asserted that his advice was intended to serve Nkrumah’s interests as leader (‘At least I can say that my advice when given is not prejudiced and, even if incorrect is given in the interests of your future’), and argued that a divided army would not necessarily be loyal to him and might threaten him, saying ‘I feel that unless the training of your Armed Services is handled with care you will not be able to rely on their loyalty, say in 1965’.

Alexander’s reaction to Nkrumah’s pursuit of ties with the Soviet Union reflects the complexities of domestic and international politics in newly independent Ghana, and in Africa more generally. Nkrumah believed in Pan-Africanism and wanted Ghana not to be exclusively aligned with either the Western or Eastern Blocs, and to pursue African unification, while the Soviet Union used African independence as an opportunity to expand its influence in the continent, and Britain sought to retain influence and prevent the growth of Communist influence. As a servant of President Nkrumah, Alexander was duty bound to follow his orders, which included drawing up plans for Ghanaianisation, but as a Westerner he sought to push Nkrumah towards adopting a more pro-Western foreign policy, while being ideologically suspicious of him. Alexander accepted the independence of Ghana and other African states despite scepticism, and produced plans for the rapid Ghanaianisation of the officer corps in compliance with Nkrumah’s instructions, but expressed opposition to Nkrumah’s plans to rapidly expand the Armed Services and train cadets in the Soviet Union. Despite opposing Nkrumah’s plans to train officers in the Soviet Union because of a desire to retain Western influence and prevent the growth of Soviet influence, he argued that the plans would harm the effectiveness of the Armed Service and also potentially threaten Nkrumah’s authority, indicating that he sought to establish his loyalty to Ghana while attempting to steer its defence policy in a different direction from that which its leader preferred.

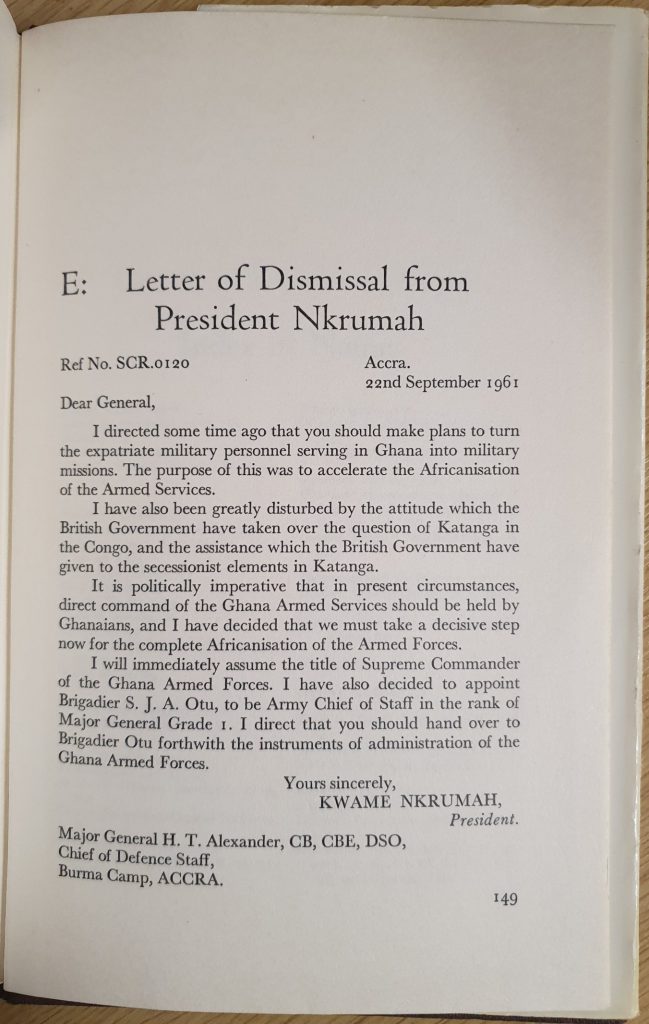

Alexander’s representations to Nkrumah were unsuccessful, and he was dismissed on 22 September 1961. In his letter of dismissal to Alexander (Figure 4), Nkrumah cited British support for the secession of Katanga in the Congo, and stated that ‘It is politically imperative that in present circumstances, direct command of the Ghana Armed Services should be held by Ghanaians’, indicating that Alexander’s dismissal was a result of a desire to accelerate the Ghanaianisation of the armed forces which Nkrumah did not feel Alexander could satisfy quickly enough, as well as the assertion of an independent Ghanaian foreign policy and suspicion of British actions in Africa. Alexander’s dismissal indicates that he was ultimately unable to balance his loyalty to Nkrumah and his desire to influence his defence policy, since Nkrumah, as the leader of an independent state, was keen to accelerate the Ghanaianisation of the Armed Services, and additionally mistrusted the British following their actions in the Congo crisis, which made Alexander’s position as a British Chief of Staff untenable.

In 1962, the War Studies Department of King’s College London was founded by Sir Michael Howard, lecturer in Military Studies and one of England’s foremost military historians. Two years later, Howard established a Centre for Military Archives at King’s to complement the new department. The Centre’s remit was simple: it would collect the papers of senior defence personnel of the twentieth century. The official launch of this archive was timed for 1964, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War. In 1973, the archive was renamed the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives in honour of Sir Basil Liddell Hart, whose own extraordinary collection of over 1000 boxes of papers is still the single largest, and one of the most often used, in the LHCMA.

2024 thus marks the LHCMA’s 60th anniversary. In those intervening years we have gathered the personal papers of over 800 senior defence personnel, and we thought this birthday year was a great opportunity to showcase just some of the items from the collection. Every month this year we will be publishing a blog post spotlighting one item or collection chosen by a member of staff. We hope you enjoy celebrating with us!

You can read last month’s post about Basil Liddell Hart’s D-Day prediction by clicking here.