By Alex Clements, Library Assistant (Collections), King’s College London

For the last year I’ve spent some of my time working at The Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives, part of King’s College London Archives. Aside from learning how the archives works and their daily routines, I also took on a more substantial project that I could complete over the course of the year.

I was to put together a boxlist of Admiral Sir Edward Charlton’s albums. Box listing is the preliminary stage before creating a comprehensive detailed catalogue entry, and the newly acquired items belonging to Read Admiral Charlton were a good fit for this task. We’d received several large albums of personal photographs, typed copies of his letters home, and contemporary newspaper clippings relating to his exploits. I had to go through these and trying to sum up as succinctly as possible the most salient information that any researcher might want when deciding to look at his papers.

I’ve been asked by the archives to sum up my thoughts on the collection, which inevitably, ended up being mostly my thoughts about the man who created them.

Edward Charlton was a man of Empire, with all the swaggering moral certainty that suggests. He was also a man of the Royal Navy, devoted to his shipmates and service. It’s also possible to strip back some of that, and see him as a person.

It’s important to remember that what we have is a self edited record. As candid as he seems about certain things – notably his views on people he deemed lesser than himself – we have only what he chose to write home about, and we cannot be certain everything was transmitted totally accurately. We know that he collected trophies and was proud of them, but we don’t know exactly how he acquired them.

One photograph of a Papuan Basiliki Islander is labelled “my love”. Edward Charlton was a funny guy. He made a lot of jokes and ironic quips throughout his letters, so considering the audience and what he says about the Basiliki islanders elsewhere, one has to assume it was a joke. At the time of this incident Charlton was on his first tour, a midshipman, and probably only just out of school.

We know specifically how the Royal Navy treated the Basiliki islanders from Charlton’s own words. They shelled them. A Chinese ship sailing under a British flag was boarded by the islanders, who were reportedly cannibals. They certainly killed all but one of the Chinese crew, who escaped. For the slight upon the flag more than any concern for the Chinese crew, Charlton’s ship sailed to Basiliki island. He describes his excitement to hunt some islanders. He does not use the word islanders. He gloats of helping to fire a shell from a state of the art naval cannon that destroys a longhouse over a mile inland. He writes of the wailing of grieving women at night.

It put me in mind of the Ghengis Khan quote – famously put into Conan the Barbarian’s mouth – in response to the question, what is best in life? “To scatter your enemy, to drive him before you, to see his cities reduced to ashes, to see those who love him shrouded in tears, and to gather into your bosom his wives and daughters.”

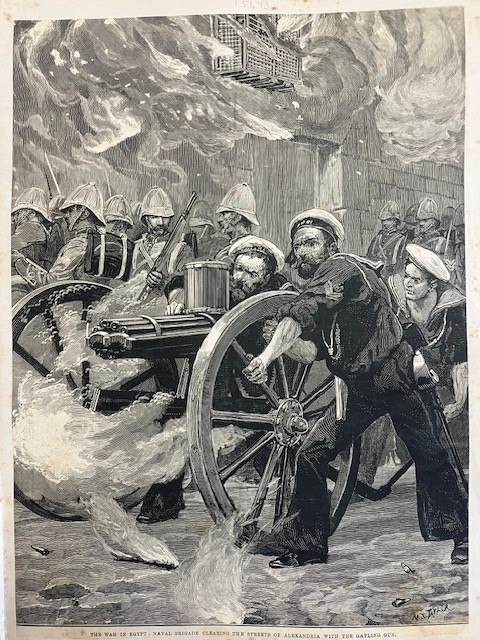

There are many accounts of both his day-to-day life and the events upon which empires turned. He served at the bombardment of Alexandria in 1882, that lead to the British taking control of Egypt, which they wouldn’t relinquish until after the Second World War. He held command of his ship during the Boxer rebellion while his captain led sailors and Marines inland. Meanwhile his ship was part of the eight nation alliance that took control of the Taku forts for the second time in what China calls its century of humiliation.

When the great slaughter of the First World War Began, much of the British Navy spent its time as a fleet in being, blockading German imports. Edward Charlton first commanded the Minesweeping boats, then was assigned command at the Cape of Good Hope station, alongside former Boer and future first prime minister of The Union of South Africa, General Louis Botha.

There are so many smaller stories within the letters. A ratting dog called Mike that swam aboard and was adopted, only to be dropped into the Yellow River after injuries he sustained in a bayonet charge at Tientsin (although that might have been another of Charlton’s little jokes, Mike was previously reported attacking people on multiple occasions, so it wasn’t for lack of esprit de corps). In a single letter he describes three boys: one discharged a pistol whilst cleaning the barrel, another died of septicaemia, a third tried to follow the second in despair but was prevented. Edward stopped in at the gravesite on subsequent visits to the port.

An image both of him and the institutions he served comes out through the collection. The sense of superiority was, from a human perspective, understandable. The Royal Navy was the largest and most powerful in the world. The British Empire at its zenith. Perhaps that is just my attempt to justify my feelings. I like Edward Charlton, and I think I even admire him. He did things that I find reprehensible, and held views that are anathema to my own. I didn’t read every letter, or understand much about his life beyond what he recorded himself. But he was charming, and loyal, and skilled at what he did. He was man of Empire, and of the Royal Navy, and a person.

My time at the archives has come to an end, but King’s staff can apply to fill in my role and I would really encourage anyone with an interest in history to do so. We have an incredible collection that has more depth than anyone could hope to understand in a single lifetime.

In 1962, the War Studies Department of King’s College London was founded by Sir Michael Howard, lecturer in Military Studies and one of England’s foremost military historians. Two years later, Howard established a Centre for Military Archives at King’s to complement the new department. The Centre’s remit was simple: it would collect the papers of senior defence personnel of the twentieth century. The official launch of this archive was timed for 1964, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War. In 1973, the archive was renamed the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives in honour of Sir Basil Liddell Hart, whose own extraordinary collection of over 1000 boxes of papers is still the single largest, and one of the most often used, in the LHCMA.

2024 thus marks the LHCMA’s 60th anniversary. In those intervening years we have gathered the personal papers of over 800 senior defence personnel, and we thought this birthday year was a great opportunity to showcase just some of the items from the collection. Every month this year we will be publishing a blog post spotlighting one item or collection chosen by a member of staff. We hope you enjoy celebrating with us!

You can read last month’s post about the Ironside Diaries by clicking here.

What do you think Charlton’s personal biases and self-editing reveal about the historical context in which he lived and worked?

Unfortunately Alex no longer is in the archive to answer your question, but there’s certainly lots of interesting things that can be pulled from this. As his article suggests, the influence of British Empire certainly seems apparent.