By Laura Burgazzi, Foyle Special Collections Library, King’s College London

In 2007 around 90,000 volumes held in the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office Library were transferred to King’s on permanent loan. The majority of this material is now stored in the Foyle Special Collections Library, where it forms the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) Historical Collection. This is the largest single collection in the Foyle Special Collections Library, and it comprises a wide range of material, including books, pamphlets and photographs. The FCDO Historical Collection covers 500 years of history, from the early 16th century until the 21st. It encompasses material on all parts of the world, though there is a particular emphasis on Britain’s former colonies and parts of the world where Britain held a strategic interest.

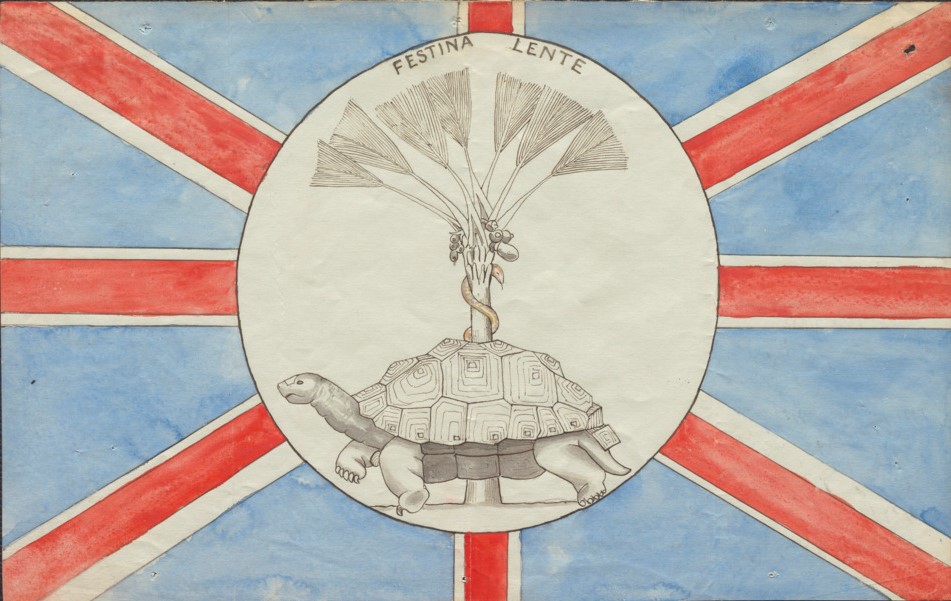

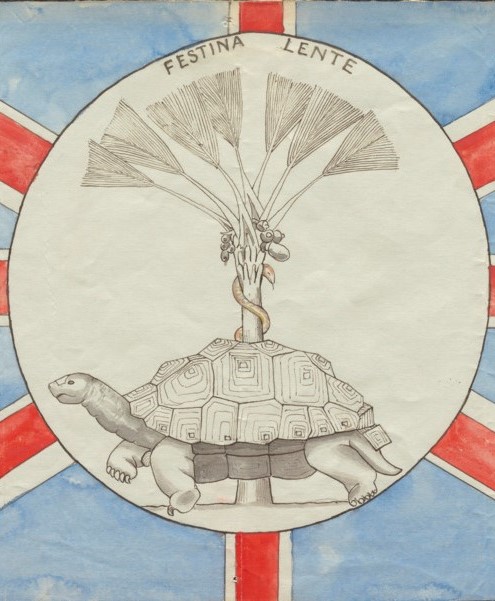

As part of my role as a Library Assistant in the Foyle Special Collections Library, I have catalogued a selection of pamphlets from the FCDO Historical Collection. These items have been extremely interesting, and one of the most interesting is this hand-drawn flag.

As part of my role as a Library Assistant in the Foyle Special Collections Library, I have catalogued a selection of pamphlets from the FCDO Historical Collection. These items have been extremely interesting, and one of the most interesting is this hand-drawn flag.

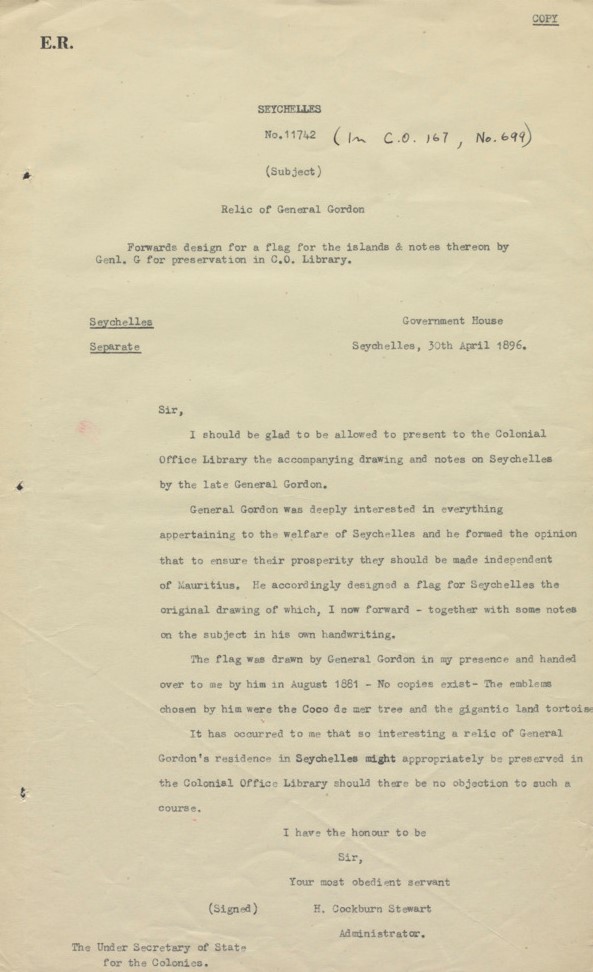

According to an accompanying letter written by Henry Cockburn Stewart (Administrator to the Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies), it is a design for the flag of Seychelles produced by Major-General Charles George Gordon (1833–85) in August 1881. Stewart’s letter outlines that Gordon drew the flag and wrote an accompanying page of notes while he was stationed in Mauritius. Stewart presented these, prefaced by his own letter, to the Colonial Office Library in April 1896.

Gordon’s Early Career

Gordon was a British army officer who had an extremely varied career. In 1852, Gordon entered the Royal Engineers, and he was subsequently posted to positions in several countries across the world, including Egypt, Romania and South Africa.

He earned the nickname ‘Chinese Gordon’ as a result of his leadership of the ‘Ever Victorious Army’ in China, which successfully defeated the Taiping rebels in May 1864. However, he is perhaps most well-known for his brutal death and beheading in Khartoum, Sudan, in January 1885; Gordon was finally killed by the Mahdists after he and his men had withstood a siege of 317 days.

Gordon developed extremely strong religious beliefs in the 1850s and 60s, while stationed in Pembroke Dock, Wales. He became a deeply committed Christian, and religion heavily influenced his worldview. He also developed a great interest in biblical geography and history.

Gordon and Seychelles

In April 1881, Gordon was assigned command of the Royal Engineers in Mauritius, where he was instructed to build forts to protect the islands from a possible Russian naval attack. He remained in Mauritius until he was promoted to major-general on 23 March 1882 and was reposted to South Africa.

Gordon was initially very negative about being posted in Mauritius. He deemed it pointless and referred to it as ‘the exile to Mauritius’ in a letter to his sister on 18 May 1881. However, his views changed quickly. Just four days later he called it ‘the pilgrimage to Mauritius’ in another letter to his sister, highlighting his religious outlook.

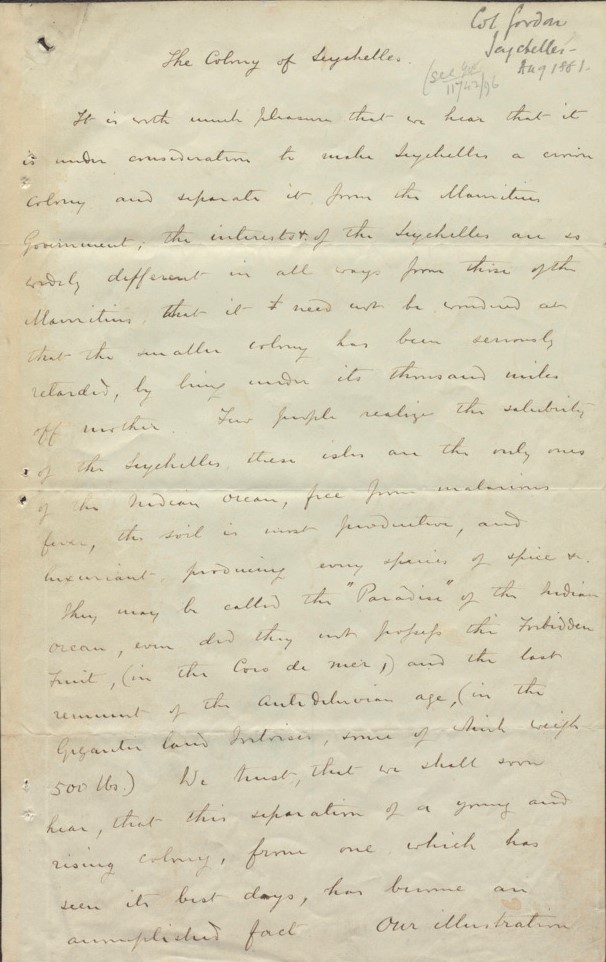

In contrast, Gordon was overwhelmingly positive about Seychelles and highlighted some of the islands’ key advantages in the accompanying notes to his flag. He emphasised its positive health aspect, stating that Seychelles was the only group of islands in the Indian Ocean free of malaria. Gordon was also clearly aware of the economic importance of agriculture in the colonies to Britain, as he intentionally emphasised Seychelles’ agricultural potential in his notes, claiming that ‘the soil is most productive, and luxuriant, providing every species of spice’. In the 19th century, many reports were conducted to investigate which colonies could profitably cultivate certain spices and crops, such as this report on Vanuatu (then referred to as the New Hebrides) produced in 1846.

Similarly, Captain Thomas Locke Lewis (c1780–1852) reported on the presence of disease in Madagascar, as well as its agricultural potential, while on a mission to the island sponsored by the first Governor of Mauritius, Sir Robert Townsend Farquhar (1810–23); a thorough analysis of this report can be found in the online exhibition, curated by Conal Priest, a King’s MA History student who undertook an internship in the Foyle Special Collections Library from January to April 2020.

Gordon stressed his support for the separation of Seychelles from the British Crown colony of Mauritius (which had governed Seychelles since 1810) in his accompanying notes. In fact, the flag was explicitly designed to be ‘adopted by the new Crown Colony of Seychelles’. Although Seychelles was not made a crown colony until 1903, Gordon states in the opening sentence of the accompanying notes that this separation was already ‘under consideration’ in 1881. He presented numerous arguments in favour of the separation, including the fact that Seychelles was ‘a young and rising colony’ while Mauritius had ‘seen its best days.’ The two countries also supposedly had ‘wholly different’ interests, though Gordon did not outline what those interests were.

In addition, he claimed that they were simply too far apart for Mauritius to be able to effectively govern Seychelles. This had been a consistent concern for British colonial administrators, as Sir Robert Farquhar argued in 1826 that although he was able to successfully eradicate the slave trade from Mauritius, he ‘could have no authority at a point so distant as the Seychelles’.

It is likely that Gordon gave his flag design and notes to a colonial administrator so that his support could be directly reported to the Colonial Office and other government officials in London. This item also highlights Gordon’s confidence that they would be separated, as he went to the trouble of designing a flag for somewhere that was not yet a separate crown colony.

Gordon’s Design

The flag’s design was carefully considered. The only standard element used was the Union Flag for the background, which reflected the fact that Seychelles would be a British crown colony. In contrast, the flag’s central badge is entirely unique. It contains a giant tortoise in front of a serpent-entwined coco de mer tree, with the oxymoron ‘FESTINA LENTE’ (make haste slowly) above. Gordon chose these elements as they symbolised Seychelles, but they also emphasise his wholly Christian worldview. Gordon firmly believed that the Vallée de Mai (now a UNESCO World Heritage Site) on the island of Praslin, Seychelles, was the Garden of Eden. He wrote numerous letters promoting this idea, many of which were extensive and included diagrams, and it undoubtedly strengthened his positive opinion of Seychelles.

The flag’s design was carefully considered. The only standard element used was the Union Flag for the background, which reflected the fact that Seychelles would be a British crown colony. In contrast, the flag’s central badge is entirely unique. It contains a giant tortoise in front of a serpent-entwined coco de mer tree, with the oxymoron ‘FESTINA LENTE’ (make haste slowly) above. Gordon chose these elements as they symbolised Seychelles, but they also emphasise his wholly Christian worldview. Gordon firmly believed that the Vallée de Mai (now a UNESCO World Heritage Site) on the island of Praslin, Seychelles, was the Garden of Eden. He wrote numerous letters promoting this idea, many of which were extensive and included diagrams, and it undoubtedly strengthened his positive opinion of Seychelles.

The tortoise represented the species of giant tortoise that is endemic to Seychelles, which Gordon called ‘the last remnant of the Antediluvian age’ in his accompanying notes. The Antediluvian age is the period in the Bible between the fall of man and the flood, and so this also clearly reflects Gordon’s Christian worldview.

Similarly, the endemic coco de mer tree was included on the flag, as Gordon believed that it was the tree of the knowledge of good and evil in the Garden of Eden, and that its fruit was the forbidden fruit consumed by Adam and Eve. Gordon wrote numerous studies outlining this argument, including an extensive study entitled Eden and its two sacramental trees, which was accompanied by multiple diagrams illustrating his idea. This study was copied multiple times by Gordon and presented to different institutions, including the Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam Botanic Garden, Mauritius. Gordon also produced multiple botanical studies on the anatomy and pollination process of coco de mer trees, which were often accompanied by scientific illustrations. One such illustration was sent to the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, as well as a specimen of the tree. It can be safely presumed that the serpent entwined on the coco de mer tree is intended to represent the biblical serpent that tempted Eve to consume the forbidden fruit.

Conclusion

Henry Cockburn Stewart declared in his typewritten notes that no copies existed of Gordon’s flag. However, this is not the case. It is possible that our flag was the original design and had not yet been copied by the time Stewart presented it to the Colonial Office in 1896, but it is now evident that multiple copies (with very slight differences to our flag) were produced.

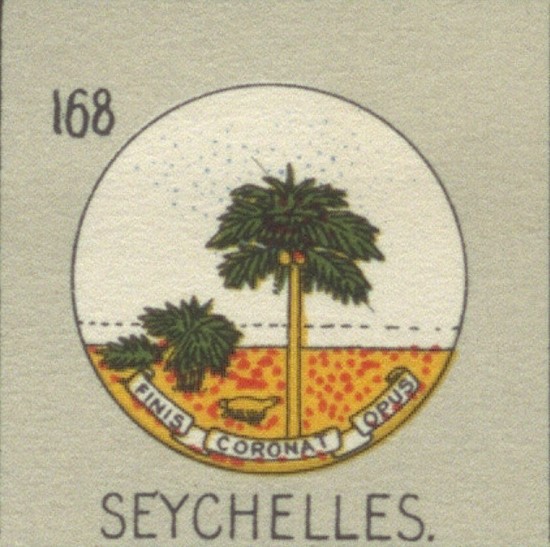

Upon the separation of Mauritius and Seychelles in 1903, Seychelles was granted its own flag and coat of arms. These were almost identical to the design of the central badge on Gordon’s flag. Although the serpent was removed and the adage was changed from festina lente to finis coronat opus (the end crowns the work), the giant tortoise and coco de mer tree remained, as can be seen in this depiction of the arms produced in 1952.

Upon the separation of Mauritius and Seychelles in 1903, Seychelles was granted its own flag and coat of arms. These were almost identical to the design of the central badge on Gordon’s flag. Although the serpent was removed and the adage was changed from festina lente to finis coronat opus (the end crowns the work), the giant tortoise and coco de mer tree remained, as can be seen in this depiction of the arms produced in 1952.

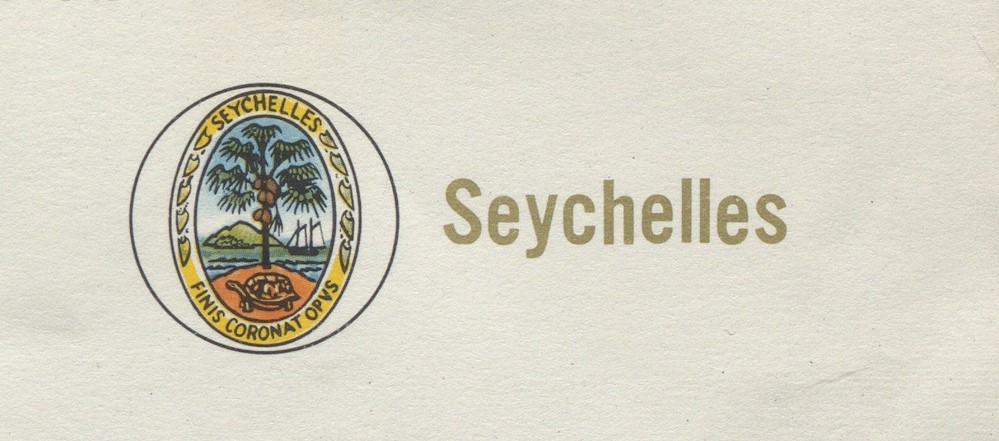

Several elements have been added to the central element of the coat of arms since 1903. In 1961, a schooner and an island were added, and the giant tortoise was returned to his prominent position in front of the coco de mer tree, as can be seen on this item produced in 1962. In 1976, the coat of arms was expanded with further elements surrounding the central badge. Nevertheless, the central badge still retains the giant tortoise and coco de mer tree as chosen by Major-General Gordon in August 1881.

Several elements have been added to the central element of the coat of arms since 1903. In 1961, a schooner and an island were added, and the giant tortoise was returned to his prominent position in front of the coco de mer tree, as can be seen on this item produced in 1962. In 1976, the coat of arms was expanded with further elements surrounding the central badge. Nevertheless, the central badge still retains the giant tortoise and coco de mer tree as chosen by Major-General Gordon in August 1881.

Bibliography

Blackmore, Stephen et al, ‘Observations on the morphology, pollination and cultivation of coco de mer (Lodoicea Maldivica (JF Gmel) Pers, Palmae)’, Journal of Botany (2012), pp. 1–13.

Davenport-Hines, R, ‘Gordon, Charles George (1833–1885), army officer’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, [retrieved 3 Sep 2022]. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-11029

Faught, C Brad, Gordon : Victorian hero (Washington, DC: Potomac Books Inc, 2008).

Gordon, Charles George, Letters of General CG Gordon to His Sister, MA Gordon (England: Macmillan and Co, 1888).

House of Common Debate 09 May 1826, vol 15, cols 1037-47.

Lionnet, Guy, Coco-de-mer : the romance of a palm, 3rd ed ([Mauritius?]: Printed by Imprimerie Saint-Fidèle, 1973).

Papers relating to Her Majesty’s colonial possessions: reports for 1877, 1878 and 1879 (London: Printed by George E Eyre and William Spottiswoode, 1880).

Religious writings of Charles Gordon, GBR/0115/RCS/RCMS 16, Cambridge University Library.