This post is written by Sergio Alonso Mislata, Library Assistant in the Foyle Special Collections Library.

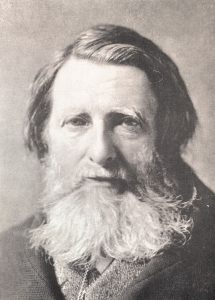

The 8 February 2019 marked the bicentenary of the birth of John Ruskin (1819-1900), and I thought it would be unfair to let this go unmentioned, if only because there are some threads that link Ruskin to King’s College London.

Ruskin was the star art critic of his time: he was a fervent supporter of JMW Turner (1775-1851) and the Pre-Raphaelites; and had an important influence on William Morris (1834-96) and the Crafts Movement. He also had an enormous impact on the Gothic Revival.

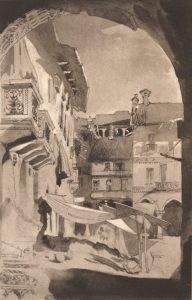

With his passionate defence of the fragile architectural styles he saw in danger of disappearing across Europe, he established the spiritual foundation for conservation and heritage enterprises to follow. He was also a skilled draughtsman and watercolourist.

As well as being an art critic and academic (he became the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford in 1869), he wrote about many other subjects and was a distinguished advocate for social causes. This is not to say that there were not also shadows in his life, and that he did not have a complex personality.

Ruskin and King’s College London

According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Ruskin attended lectures at King’s (established 1829) during 1836, before he went into residence at Christ Church, Oxford, in 1837.

As a background to this most direct link to King’s, between 1833 and 1835 Ruskin had attended a school run by the Anglican priest Thomas Dale (1797-1870) of St Matthew’s Chapel in Denmark Hill. Thomas Dale was appointed professor of History and English Language at King’s in 1836 and Ruskin followed.

The second visible link of Ruskin to King’s has just been hinted at: he spent his childhood and an important part of his adult life in the Camberwell area, between Herne Hill and Denmark Hill, not far away from where King’s Denmark Hill Campus is located today. People familiar with the area will know that the name of the beautiful park that neighbours King’s College Hospital is no other than Ruskin Park.

Another connection with King’s is found in the King’s College London Archives where letters (and copies of letters) written by Ruskin to author George MacDonald, a King’s alumnus himself, and to Edgar Prestage, who would later become the first Camões Professor of Portuguese at King’s, can be found.

Items in our collections related to Ruskin

Most of the items by or about Ruskin in the Foyle Special Collections Library belong to either the Miscellaneous Collection or the Adam Collection. Items from the Adam Collection were part of the personal library of Romania-born literary editor Miron Grindea (1909-95). Below are some notable items which we hold in our collections.

The first of these is The poetry of architecture (a collection of articles from the Architectural magazine, 1837-38, published as a book in England in 1893). In this book, Ruskin argues that the basis of all grace and the essence of beauty in architecture is a:

unity of feeling … its adaptation to the situation and climate in which it has arisen … its strong similarity to, and connection with, the prevailing turn of mind by which the nation who first employed it is distinguished

And much to his regret he feels he needs to highlight that the excesses and incongruence of English modern architecture denote an ignorance of this principle:

We have Corinthian columns placed beside pilasters of no order at all, surmounted by monstrosified pepper-boxes, Gothic in form and Grecian in detail, in a building nominally and peculiarly national

For this, he blames not only the architects who will not make an effort to capture the poetry of architecture. He wants to also appeal to the average person who lets the state of things go on unchecked with their passivity:

in a climate like ours, those few who have knowledge and feeling to distinguish what is beautiful, are frequently prevented by various circumstances from erecting it. John Bull’s comfort perpetually interferes with his good taste, and I should be the first to lament his losing so much of his nationality, as to permit the latter to prevail.

In Unto this last (1862), a book comprising articles about political economy published in Cornhill magazine in 1860, Ruskin says of these articles ‘I believe them to be the best, that is to say, the truest, the rightest-worded, and most serviceable things I have ever written; and the last of them, having had especial pains spent on it, is probably the best I shall ever write.’ The pamphlet The rights of labour according to John Ruskin (1889), consists of excerpts of Unto this last arranged by Thomas Barclay.

The crown of wild olive: four lectures on industry and war 1912), comprises not only the 3 lectures included in the 1866 first edition of the book, entitled, ‘Work‘, ‘Traffic’, and ‘War’, but also a fourth lecture entitled ‘The future of England’, with the appendix ‘Notes on the political economy of Prussia’.

Special Collections also holds some exhibition catalogues related to Ruskin:

- the catalogue of Ruskin a Verona, an exhibition that took place in 1966 at the Museo di Castelvecchio, Verona;

- a catalogue relating to the 1955 Wildenstein Gallery exhibition held in London about Marcel Proust, organised by the French Direction des Relations Culturelles;

- the 1956 Whitworth Art Gallery exhibition held in Manchester and entitled

Marcel Proust 1871-1922: an exhibition of manuscripts, books, pictures and photographs

These two final exhibition catalogues include the essay ‘Proust and Ruskin’, by Marie Nordlinger-Riefstahl, which discuss the influence of Ruskin on Proust – the Frenchman being a notable translator of Ruskin.

Other publications about Ruskin include A disciple of Plato: a critical study of John Ruskin, by William Smart (1883), and a chapter (written by RH Wilenski) dedicated to him in the book The great Victorians (1932).

More works by and about Ruskin can be found at the Maughan Library, including his most famous works: Seven lamps of architecture (first published in 1849) and The stones of Venice (first published between 1851-53).

I hope this brief overview has managed to spark your curiosity and that some of you might decide to use our wonderful resources to delve deeper into Ruskin’s work and life. A few final words by Wilenski to perhaps fuel this possibility:

There was a good deal of Cockney impudence in Ruskin; he was vain, conceited, and arrogant; and judged by modern standards, he was inadequately educated in most of the fields in which he worked … But he was a great man all the same. He is commonly regarded as a sentimental moralizing aesthetician. He was nothing of the kind. He was a man of action, who was condemned by an unlucky accident to act for the most part by means of words and sentences …

Select bibliography

France. Direction des Relations Culturelles. Marcel Proust and his time, 1871-1922. London: Wildenstein Gallery, 1955 [Adam Collection PQ2631.R63 F68]

R Hewison. Ruskin, John (1819–1900), art critic and social critic. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. Retrieved 4 Apr. 2019, from http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-24291

Terence Mullaly. Ruskin a Verona. Verona: Museo di Castelvecchio, 1966 [Adam Collection NC242.R8 M85 MUL]

Marcel Proust, 1871-1922. An exhibition of manuscripts, books, pictures and photographs. Manchester: Whitworth Art Gallery, 1956 [Adam Collection PQ2631.R63 Z725]

John Ruskin. The crown of wild olive: four lectures on industry and war. London: George Allen & Sons, 1912 [Adam Collection PR5255 RUS]

John Ruskin. The poetry of architecture. London: George Allen, 1893 Miscellaneous Collection FOL. NA2550 RUS]

John Ruskin. The rights of labour according to John Ruskin. Leicester: Chas D Merrick, [nd] [Miscellaneous Collection PAMPH. BOX HD8390 RUS]

John Ruskin. Unto this last. London: George Allen & Sons, 1912 [Adam Collection PR5261 RUS]

William Smart. A disciple of Plato: a critical study of John Ruskin. Glasgow: Wilson & McCormick, 1883 [Miscellaneous Collection PR5267.P5 SMA]

RH Wilenski. ‘John Ruskin’, in The great Victorians. London: Ivor Nicholson & Watson Ltd., 1932 [Hamilton Collection DA562 MAS]