The post below is made on behalf of Charlotte Chambers, who is undertaking the Early Modern History MA course at King’s. From January to April 2018, Charlotte was an intern in the Foyle Special Collections Library, working with our early printed books.

As part of my Early Modern MA History course at King’s College London, I had the opportunity to become an intern in the Foyle Special Collections Library, working with their incunabula collection. Incunabula is the term used to refer to books printed before 1501.

My interest in studying incunabula revolved closely around the invention of the printing press, and the recurring argument that it was the development from manuscript to print which sparked the transition from the medieval period into early modernity. This argument was always in the back of my mind throughout the experience and helped my engagement with the source material.

Studying the early origins of the printing press led me into new territory and provided a new means of answering the all-encompassing early modernist question of where the progression towards modernity began. My historical period of interest is usually the 16th century. Thus, it was enlightening to have access to both late medieval and early modern sources to evaluate and determine this change for myself.

The core task of the internship was to study the provenance of the incunabula books in the collection, and to update the information on the CERL (Consortium of European Research Libraries) Material Evidence in Incunabula database. The purpose of MEI is to create a map tracing how incunabula have travelled across Europe throughout the centuries. The history of each book begins from the place of printing and ends with how they became housed in their current institutions.

I was invited to a training day at the British Library where I spent the day learning how to use the database and discussing my findings with the curators also present. I found the experience to be rewarding as I acquired new skills and had the opportunity to discuss my research and ideas.

The purpose of the internship was to work closely with the incunabula collection by analysing and researching the provenance of the books. When studying incunabula, the provenance of a book is of great interest. From hand-written notes to illustrations, what may first appear as a book lover’s nightmare, becomes an absolute dream when studying the ownership history of incunabula. The marks can lead one down a variety of historical pathways and provide as many new questions as answers. The printing press revolutionised the early modern world but the blemishes left behind on these works from past owners can also often hold evidence and history themselves.

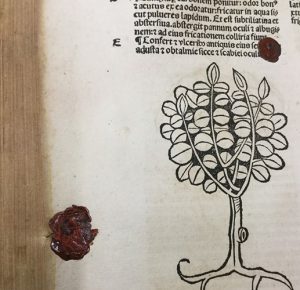

For example, on the 63rd leaf of Special Collections copy of the 1497 Hortus sanitatis is a wax seal, which is unusual in nature and placement. The mystery of the seal was further interrogated when two letters, dated 12 and 15 January 1948, were discovered at the back of the book. The letters show correspondence between a former owner, Dr Fleming and Howard Nixon of the British Museum, discussing the provenance of the seal.

For example, on the 63rd leaf of Special Collections copy of the 1497 Hortus sanitatis is a wax seal, which is unusual in nature and placement. The mystery of the seal was further interrogated when two letters, dated 12 and 15 January 1948, were discovered at the back of the book. The letters show correspondence between a former owner, Dr Fleming and Howard Nixon of the British Museum, discussing the provenance of the seal.

Nixon’s original theory was that the seal was a printer’s mark, added to the batch of paper before printing took place. However, in his following letter, the red residue of wax found above the seal disproves his theory. The wax is covering the printed text, suggesting it would have had to have been made after printing had taken place.

This red residue of wax asks questions regarding the provenance of the book and the purpose of the seal. Though these letters may not be part of the book itself, they contribute to the rich tapestry of its history. After these letters there is no evidence of a further correspondence, and 80 years have passed since Nixon’s responses and the seal remains a mystery, with numerous questions having yet to be solved. Is the seal a printer’s mark after all, and the spilled wax above was made on a later date, or was a previous owner practising their own seal?

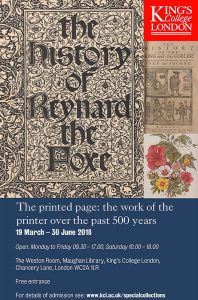

From the research I accumulated on the provenance of incunabula, I was asked to contribute towards the curation of an exhibition: The printed page: the work of the printer over the past 500 years, alongside members of Special Collections staff. The purpose of my contribution was to introduce the incunabula collection and the first age of printing with moveable type, to fellow students, staff and visitors to the exhibition.

This experience allowed me to showcase my research and share my new found understanding, whilst learning the skills needed to curate exhibitions. It also allowed for me to work closely with the Special Collections staff, and gain insight into their specific areas of study. The exhibition is currently on display in the Maughan Library, Weston Room.

Overall, the Foyle Special Collections Library internship allowed for me to work closely with a variety of sources, covering a variety of topics, across my period of interest. This allowed for me to further develop my practical and theoretical approach to print culture and analyse how it became a central factor within early modern society.

Overall, the Foyle Special Collections Library internship allowed for me to work closely with a variety of sources, covering a variety of topics, across my period of interest. This allowed for me to further develop my practical and theoretical approach to print culture and analyse how it became a central factor within early modern society.

Through taking part in the internship programme, I have gained valuable skills in how to use the source material and how to communicate these findings successfully – skills that are transferrable to my academic career.

The project was challenging, demanding and above all an achievement in completing. The main concepts I will take away from studying incunabula is that these items are not just a product of the invention of print, but they elucidate the beginnings of a centralised print culture, show how print has preserved our history, and indicate how printed material will continue to contribute to future historical research.

The pages of the incunabula books I studied may have been printed in the late 15th century; but the items and their associated provenances will remain to tell a story in the centuries to come.