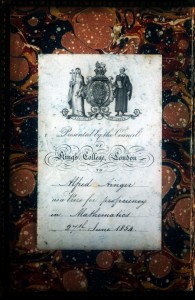

On 27 June 1854 when seventeen year old Alfred Ainger (1837-1904) picked up his prize for ‘proficiency in Mathematics’ from King’s College London, was he surprised to discover that it was a handsomely bound volume of the complete works of William Shakespeare edited by Charles Knight, complete with the college arms stamped in gold on its cover? [tape was required eventually]

To me a connection between a mathematics prize and the complete works of Shakespeare is not obvious.

To me a connection between a mathematics prize and the complete works of Shakespeare is not obvious.

Was this prize selected with Ainger in mind or is it the default prize for any number of achievements, so that the prize reflects the enormous esteem in which the Victorians held Shakespeare?

And did this prize have a career-altering effect? The following year, when he was 18, the Dictionary of National Biography reports of Alfred: ‘Devotion to Shakespeare manifested itself early and in 1855 he became the first president of the college’s Shakepeare Society’.

In fact, in later life it is his literary skills, not his mathematical ones, for which Ainger would be recognised. He went to King’s school with the sons of Charles Dickens and was taken up by the novelist for his skill in amateur dramatics. He knew Tennyson, became a published authority on Charles Lamb, and, along with producing books, articles and lectures, became an Anglican preacher and chaplain both to Queen Victoria and subsequently to King Edward VII.

His prize Shakespeare volume is quite new to our collection (2016), but already the engravings by William Harvey have provided illustrations for an exhibition I was assembling in January from King’s College London Archives to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death.

King’s has not been around yet quite 200 years, so the Archive might not expect to have much relevant to Shakespeare (1564-1616). Fortunately just over a century ago Fredrick Furnivall (1825-1910) the prolific Victorian scholar, literary editor, lexicographer and rowing enthusiast donated to King’s, along with his impressive library, a collection of papers from the many societies he founded. The New Shakspere Society papers (Furnivall insisted on the variant spelling) proved a good source for Shakespeare in the archives at King’s, the frontispiece from Ainger’s Shakespeare providing the opening illustration.

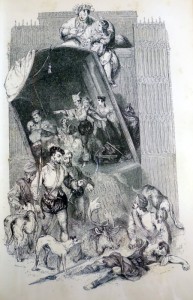

Each play has a full-page illustration in the volume and it is intriguing to see how an entire play is squeezed into a single frame for such pieces as the Taming of the Shrew where the Sly framework literally frames an inner scene from the shrew taming when Kate and Petruchio encounter the tailor and haberdasher meant to provide her wardrobe. The insanity of the comedy is conveyed visually by setting the inner frame at a dangerous angle.

Each play has a full-page illustration in the volume and it is intriguing to see how an entire play is squeezed into a single frame for such pieces as the Taming of the Shrew where the Sly framework literally frames an inner scene from the shrew taming when Kate and Petruchio encounter the tailor and haberdasher meant to provide her wardrobe. The insanity of the comedy is conveyed visually by setting the inner frame at a dangerous angle.

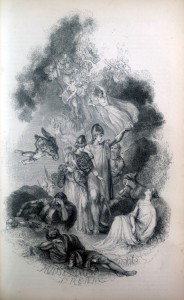

The four interwoven layers of A Midsummer Night’s Dream are stacked on top of each other with the young lovers at the bottom being awakened by hunters Theseus and Hippolyta in the middle of the image while Oberon and Titania and their flight of fairies crowd the upper region with Puck flying in from the left carrying the ass’s head taken from Bottom the Weaver. The tone is as romantic as anyone could wish.

The four interwoven layers of A Midsummer Night’s Dream are stacked on top of each other with the young lovers at the bottom being awakened by hunters Theseus and Hippolyta in the middle of the image while Oberon and Titania and their flight of fairies crowd the upper region with Puck flying in from the left carrying the ass’s head taken from Bottom the Weaver. The tone is as romantic as anyone could wish.