World Breast Feeding week (#WBW2020) passed me by! It only came to my attention on Friday, meaning this is a bit belated!

#WBW2020 focused on the environmental impact of infant feeding and the need to promote and support breastfeeding for the health of our planet and its people.

Breastfeeding protects the health and well-being of mothers and babies. There are also economic and social benefits. Increasing the rates of breastfeeding worldwide will help us meet the UN’s global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—including Goal 5 on gender equality and women’s empowerment. Women have the right to bodily autonomy, meaning they have the right to make decisions about their bodies with accurate information, free from fear, external pressures and discrimination, including whether to breastfeed and for how long. People who wish to breastfeed should have the right to do so—whenever and wherever they choose—with the full support of their families, communities, employers, and governments.

While my main focus is on breastfeeding cis mothers (ie. mothers of my own experience), I thank Nicole Robinson (who alerted me to #WBW20) for the intersectional and inclusive resources she shared with me. Many trans men, transmasculine and non-binary people chestfeed. You can read about one experience here: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2016/08/chestfeeding/497015/

Plus, it is also possible for trans women and non-binary people to feed their babies through relactation, with the first successful documented case in 2018: https://www.llli.org/breastfeeding-info/transgender-non-binary-parents/

This can also support adoptive parents in feeding their babies and is especially helpful for allowing little ones who have previously been breastfed by a birth parent to continue doing so.

There is a popular misconception that breastfeeding is free and easy. In fact, it requires access to trained counsellors and time to breastfeed or express milk. This misconception initially provoked this blog. Women face multiple barriers to breastfeeding in the home, community, health care system and workforce. Indeed, millions of mothers around the world stop breastfeeding before they want to because they do not get the support and time they need to continue.

The reasons why women avoid or stop breastfeeding range from the medical, cultural, and psychological, to physical discomfort and inconvenience.

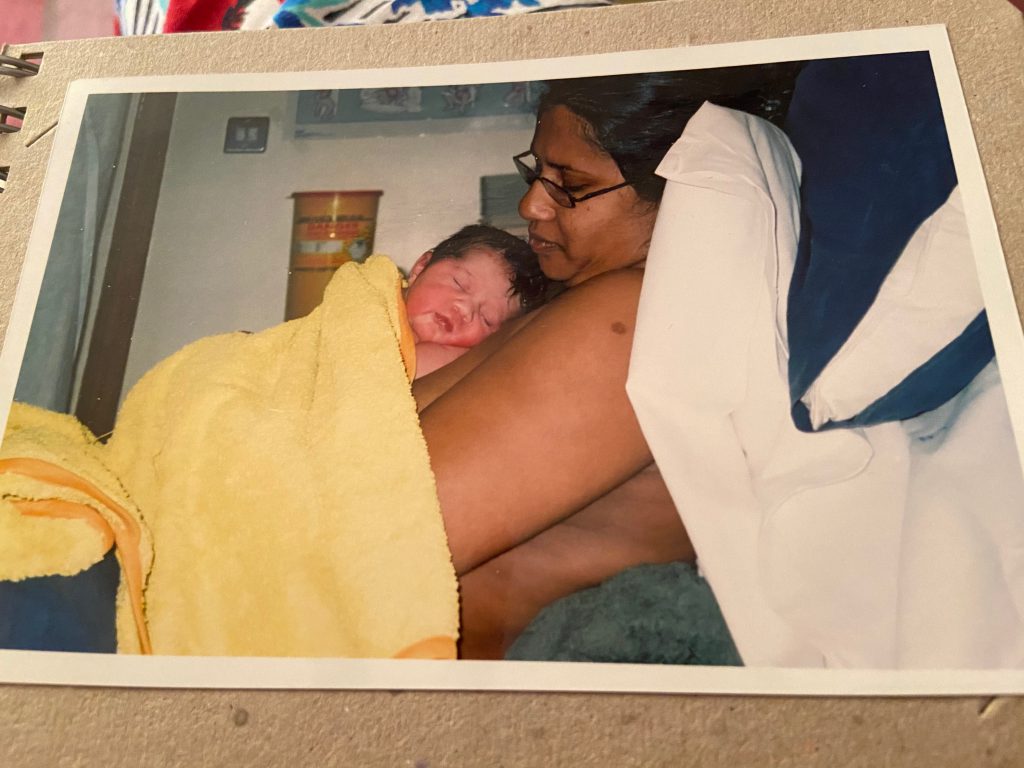

I will never forget those early hours when Kaela (now 16) was born, and how internally terrified I had become about whether I would be able to breastfeed. It took me several weeks to get competent at it. I remember being at my wit’s end when my health visitor visited one day. I had basically become welded to the sofa, with baby, pillow etc in arms, never being sure if she was getting any sustenance, ultimately feeling exhausted and unable to see how this could be sustained for 6 more minutes – let alone 6 more months.

My health visitor, Juliet, was patient and trained. She sat with me. She supported and comforted me and, most of all, she advised me expertly. I never became one of those mums that were able to breastfeed in any circumstance, who seemed perfectly comfortable walking around, or just ‘popping baby on’. I always needed to sit down. I always needed to feel comfortable and have my ‘stuff’. But I was very pleased to successfully feed K for just over 6 months (and Lyra after her) and had every intention of continuing beyond 6 months, when she decided she had had enough.

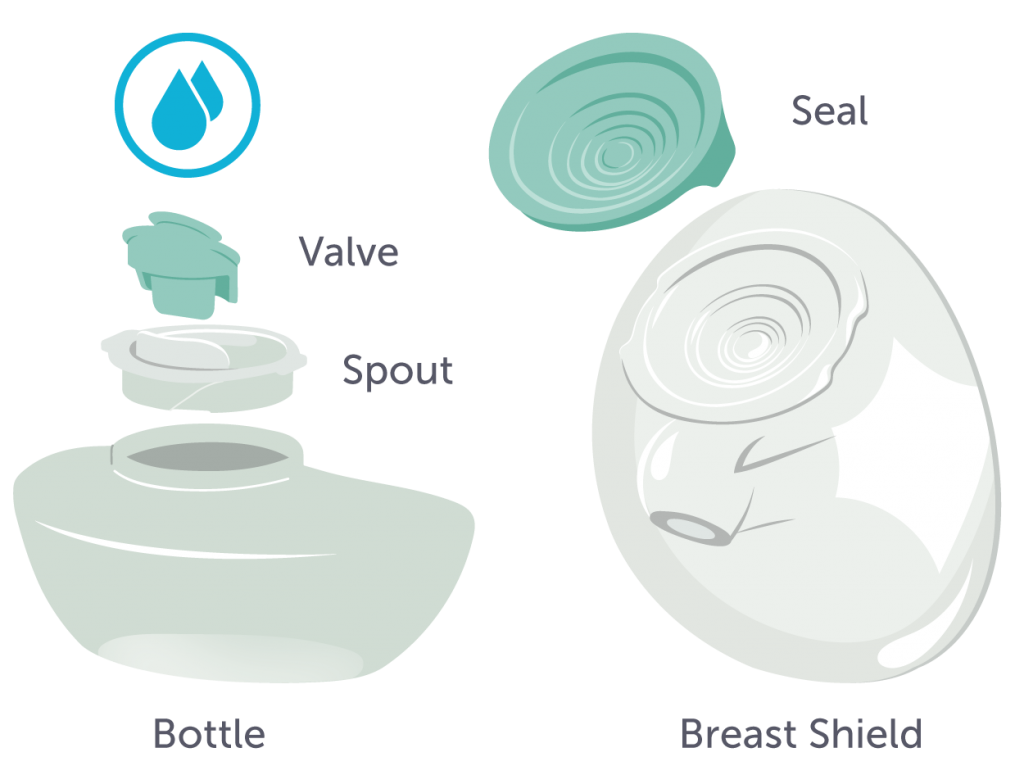

I also remember many horrible hours of expressing. I hated the whole experience for a few trickles into the little freezer bags. I was also so paranoid about all the storage requirements. Kaela actually refused to ever drink from a bottle, so it was also an utter waste of time! I was really struck when I read Caroline Criado Perez’s Invisible Women; about Janica Alvarez’s experience trying to raise money to finance a new kind of breast pump and being treated with disdain.

So much of my experience was marred by the horrid nature of the breast pump itself! I am joyous for those women who come after me and get the joy of Elvie’s silent wearable breast-milk pump (which also made it into the 2019 Oscars’ swag bag). It an example of the difference that can be made if women are included in product design.

Society and HE needs to invest in programmes and policies that put women’s rights, dignity and choice at the centre. Supporting a woman’s right and ability to breastfeed is a measure of gender equality—and building a breastfeeding-friendly society is everyone’s responsibility.

As a university committed to Athena SWAN’s gender equality charter mark, we support policies and programmes that ensure breastfeeding and chestfeeding parents have access to good nutrition and can nurse their babies for as long as they want through our service strategy. We can use our platform as a world class research institution to ensure women’s and parents’ (whether mothers or otherwise) voices are heard and included in developing research and its findings. Breastfeeding parents make enormous contributions to the health and prosperity of families, economies, and nations. Still, the benefits of breastfeeding remain largely hidden and undervalued. We can change that, but we must respect women’s and parents’ agency by treating them as partners, decision makers and rights-holders first and foremost. And obviously for staff and students who are parents we can provide practical support. We have several parenting rooms, a parent and carer’s hub and a working family subscription for all King’s community to use.