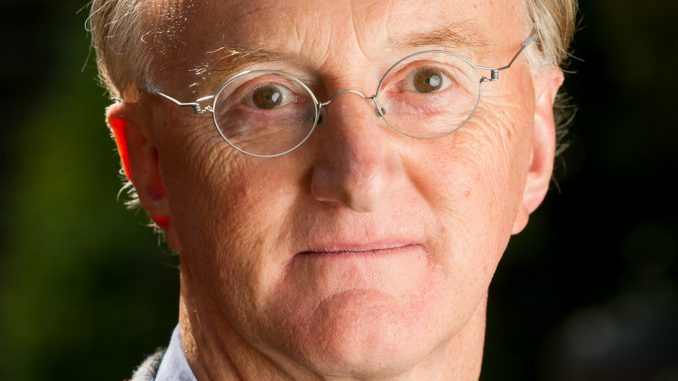

As the funding period for NIHR CLAHRC South London comes to an end this month, the CLAHRC Director Professor Sir Graham Thornicroft shares his reflections over the past five years and his plans for the new NIHR Applied Research Collaboration South London.

Why did you want to lead CLAHRC South London, with its focus on applied health research?

My interest in leading the CLAHRC began because at last it gave us the opportunity to think systematically about putting evidence into practice. I say at last, because quite often, we see a rather superficial view expressed that research will somehow contribute automatically towards the betterment of society. We are then left with a huge gap between what researchers do and what actually goes on in the real world of health and social care practice – with no detailed attention to all of the many elements that need to reliably connect to close that gap. The CLAHRC was deliberately intended to help us to identify what are the component parts, and how they need to synchronise, for the links from evidence to practice to really connect. In terms of leading the CLAHRC, I have gained a lot of reward and satisfaction from doing my best to construct teams of people who have highly complementary skills, and then enabling them to flourish and to do great quality applied research.

What did you want CLAHRC South London to achieve when it was established in 2014?

We came at the CLAHRC setting out a series of deliberately ambitious targets. Until 2014, when we started, the phrase ‘implementation science’ was hardly understood in the UK. Indeed, there was a great deal of scepticism about whether this was anything to do with real science or real research. Now, just five years later, that situation has been transformed. We are now seeing much greater interest in this field, and after we established the Centre for Implementation Science at King’s College London, we’re seeing other similar centres being set up. We now also see funding calls specifically for implementation science projects and programmes. We were an early adopter in the field, and we’ve been going from strength to strength ever since.

When we started the CLAHRC we also committed to creating a master’s course to support people learning these implementation and improvement science skills, which we did just a year after the CLAHRC began.

One of the hallmarks of the new approach which we wanted to implement wasn’t just teaching researchers new types of research skills. It was also reaching people from a range of backgrounds, especially clinical and managerial staff such as those working in quality improvement and quality assurance roles within the health and social care services – and this development has been very rewarding to see.

What has been the most surprising or interesting thing that you’ve learnt over the past five years?

First, I think one of the elements which has particularly struck me is the growing appreciation of the importance of implementation science and its applicability across the world. These research methods are also applicable across the whole range of health and social care challenges and needs, whether in relation to people at the end of life receiving palliative care, to people who have had a stroke, or people with alcohol addiction.

Second, we have also deliberately introduced the requirement that all the work of the CLAHRC must have strong patient and public involvement. That was a point of principle, but it’s also a point of practice. In principle it’s right, because they are the intended beneficiaries of the CLAHRC’s work, whether we see that in terms of clients or consumers or patients or service users. People who have health or social care difficulties and their family members are in many ways the best informed about the challenges they face and what forms of treatment, care and support may be of help to them. If we don’t systematically bring these groups into the equation then we are likely to be proposing interventions, treatments and services which are partially or fully irrelevant. But it’s also important in terms of how services are delivered. This is especially important in south London where we have very many different communities and cultures represented, and where we have to be very thoughtful to make sure that the offer, whether it be of health or of social care, is acceptable and is relevant to different social and sometimes faith communities which we try to serve.

What are you most proud of at CLAHRC South London?

The CLAHRC has produced a wide and rich array of achievements. It is sometimes invidious to name one or the other without recognising all. But if you were asking me to pick one area which I think is important it would be capacity building. When we began the CLAHRC, we had no provision for teaching and training researchers, clinical staff, and patients and public members, about how to go about researching questions around implementation. We’ve seen a huge explosion of such work in the years since the CLAHRC started. For example, we’ve set up a summer school with over 100 people from dozens of countries across the world coming together, supported by an enormously experienced international faculty. The best experts in the world gather each year at our Masterclass in London to teach implementation science skills, especially to help early and middle career colleagues to learn and apply these methods. This has now expanded to the extent where in 2020, we will have the third annual Implementation Science Research Conference in the same week as the Masterclass. This is being brilliantly led by Professor Nick Sevdalis and his colleagues. This work is strongly supported by the CLAHRC capacity building theme led by Dr Rachel Allen and this has exceeded my expectations about the reach, volume and quality of our capacity building work. So, I think that’s one jewel in the crown, among many others.

What have been the greatest challenges and how have they been addressed?

I think that one of the issues is to continue to look to the long term in terms of implementation and service improvement, which can be challenging when colleagues in our NHS Trust partner organsiations face year on year budgetary constraints. A related issue is that to quite a large extent the ways in which research and knowledge can be used within clinical and social care practice settings, depends upon the density and trust placed in the relationships between the different participants, in this case, for example, researchers, clinical staff, social care staff and managers. What we’ve found in recent years is that the senior staff at some of our partner organisations have been changing fairly rapidly and that means that one needs to form relationships with senior colleagues and then if they change, form new relationships with new senior colleagues and so on. This is absolutely required but it does mean an investment of time to form and then reform those active and collaborative relationships with senior colleagues in our partner organisations.

I think another challenge, but also an opportunity, is the changing nature of arrangements for both commissioning and providing primary, community and social care services. We are now in a period of very significant structural change with respect to clinical commissioning groups and our sustainability and transformation partnerships, including integrated care systems in south London. This is changing the entire commissioning and service provision landscape. In this respect we have a tremendous strength in that one of the co-chairs of the CLAHRC Board, Dr Adrian McLachlan, is the chair of the Lambeth Clinical Commissioning Group, who is able to frequently keep us up-to-date with those elements of the changing local arrangements which are designed to improve patient care.

Lastly, what are your hopes for the Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) South London and how will it be different to the CLAHRC?

The ARC (despite the similar name!) is a different programme of work from its predecessor, the CLAHRC. There are a number of important distinctions. First, we are now required to emphasise the importance of social care as well as healthcare in the provision for local people. In fact, we have a whole new theme of work led by Professor Jill Manthorpe to explicitly address these issues.

Second, we have to show that we are fully aligned and embedded within local public health priorities and practice, again, led by the local authorities and we address this with a strong public health theme led by Professor Peter Littlejohns and by welcoming Professor Kevin Fenton, Strategic Director of Place and Wellbeing for Southwark Council to the ARC Board. The third big distinction is that we’re adding a new research theme focusing on the health of children and young people, led by Dr Ingrid Wolfe. This brings a vital new dimension to the life-course approach, which we’re explicitly adopting in the ARC programme.

The fourth important change is that ARCs are required not just to do research, but also to have an additional element within the programme called an implementation theme. We have enormous strength here because of our long-lasting and strong relationship with our academic health science network in south London, the Health Innovation Network (HIN) and, in particular, Zöe Lelliott, the HIN’s Acting Chief Executive Officer. Zöe has been a strong collaborator in the work of the CLAHRC from the very beginning. She will be leading the implementation team at the ARC, working closely with Dr Natasha Curran, the HIN’s Medical Director. This will reinforce our commitment to do everything that we can to see that the knowledge we generate in the ARC will feed through to improvement of local practice, and then through to better health and social care outcomes for people living in south London.

Leave a Reply