Peter Littlejohns, deputy director of the CLAHRC and public health theme lead explored the concept of the “hidden patient” in controversial health prioritisation decisions, at the International Society for Priorities in Health’s bi-annual conference.

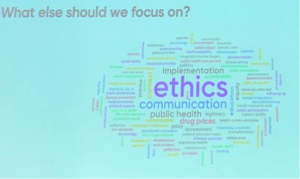

I recently visited Linkoping, Sweden, to attend the International Society for Priorities in Health (ISPH) bi-annual conference. In total, 165 delegates from 60 countries had gathered to share ideas on how to allocate health resources fairly. During the opening plenary session the delegates were invited to use an interactive app to indicate what they considered to be the most important prioritisation issues to undertake research on. The results were portrayed as a word cloud (the bigger the word the more the delegates mentioned it – see figure below) which suggests that our CLAHRC study on the ethics of prioritisation, concentrating on stakeholder engagement within a public health implementation framework is not far off the mark.

I was co-author on two oral presentations based on our CLAHRC project – the first summarising the development of the Decision Making Audit Tool (DMAT) and the second using the tool to assess the effectiveness of the concept of “accountability of reasonableness” in Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs). During my presentation I emphasised that one of the main challenges of prioritisation, which goes to the heart of its legitimacy, is when treatment is withheld from an individual or a group that is considered “needy”. This type of “case study” is nearly always newsworthy and the system is easily portrayed as “being unfair” and often triggers an adverse popular response. What is missing is the counter argument that highlights that should the “needy” patient be allocated cost-ineffective (or low value) treatment, then due to the opportunity cost incurred, many, often more needy patients would miss out on treatment and suffer. However, it is difficult to make a “cause celebre” out of these unknown patients, which I have recently referred to as the “hidden patients” (“Shining a light on hidden patients” BMJ 2018).

One possible approach is to take those cases that get into the public’s consciousness, but use them to explore issues in a more subtle and thorough way than is usually adopted by the popular press. This is a way of drawing the public’s attention to the need to prioritise health services fairly in a manner that makes sense and is relevant to stakeholders, patients and the public. In my presentation I described how, as part of the CLAHRC project, I had explored the medium of film as a means of communicating these complexities to the public.

“The lottery of devolved cancer care” uses variation in access to expensive cancer drugs in the four home countries of the UK (health care is a devolved responsibility for England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland). It is based on the circumstances that led a cancer patient Irfon Williams moving from Wales to England to get his treatment. He established a charity to raise the issues of differential access to treatment. Irfon died three months after being interviewed before he could see the final film but Becky, his widow, said on viewing it, “I think it is beautifully filmed and thought provoking to those who are outside this bubble of cancer treatment “. His autobiography “Fighting Chance” was published posthumously in May 2018.

In the film, Irfon highlights very specifically that he accepts that not all treatment can be available, but considers that a fair process needs to be in place. If this was the case, then he feels that patients, even if they did not receive their treatment, would accept that priority setting is inevitable. This is an aspect that was not covered at all during the many hours of news coverage of his circumstances and will be used to raise awareness of the need for public participation in these processes. The film was a semi-finalist in the 2017 SeeMôr Film Festival in Wales. Apparently at the ISPH’s business meeting, I am told, that the new incoming president Kjell Arne Johansson had attended my session and suggested that the Society should take up the challenge of interacting with the public through digital media, including film.

This theme was built on by Professor Lars Sandman of the Swedish National Centre for Priorities in Health during his session when he asked whether the ethics of stopping treatment are the same as not starting it in the first place.

Professor Sandman referred to the concept of the “statistical patient”, the equivalent of my hidden patient. He concluded that there was no difference in not starting and stopping. However, when I asked him if he felt the same applied to stopping whole services as compared with individual treatments, we concluded that there was little evidence on which to base a decision and that more research is needed – something that we hope to explore further.

Before leaving for home I spent a day in Stockholm and visited the Fotografiska where there is a permanent exhibition of the photography of the late Swedish photographer Lars Tunbjork. His work captures the essence of everyday Swedish life. One of his later projects was in collaboration with a writer, Goran Odbratt, when they toured around Sweden visiting welfare offices, prisons, rehabilitation clinics, day centres and social services. Anxious that Sweden’s great social welfare tradition was under threat he wanted to take portraits of the clients to make them people rather than statistics. The rationale of the resulting book “Dom alla” (them all) is explained:

All human values – justice, morals and ethics – are ultimately dependent on the presence of real human faces. If these are missing, obscured, distorted or manipulated, then there is also a lack of personal responsibility for what is going on in a particular situation, in society or in the world.

This reinforces my view that we have to bring alive the “faces” of the hidden patients if we are to make health prioritisation acceptable.

You can read my presentations here:

Does accountability for reasonableness work? The political realities of priority in the English NHS

Leave a Reply