‘We have left undone those things which we ought to have done;

and we have done those things which we ought not to have done;

and there is no health in us.’

1928 Book of common prayer

On the 4 July this year, the day before the NHS’s 70th birthday, NHS England launched a consultation on their list of interventions that the NHS should cease to offer on a routine basis – part of its side of the bargain to ensure that the NHS is as “efficient” as possible having had its budget increased by 3.4%. The press release announced that:

“NHS England has today set out plans to curb ineffective or risky medical treatments given to hundreds of thousands of patients each year. […] to stop or reduce routine commissioning of 17 interventions, including breast reductions and snoring surgery, where less invasive, safer treatments are available and just as effective. The plans for consultation are the first step in a new programme to prevent unnecessary pain and inconvenience, curb waste and free up resources for frontline care, and have been developed with and are supported by partner organisations including leading health professionals. Patients would be spared more than 100,000 unnecessary procedures a year, freeing up an estimated £200 million that can be spent on more effective treatments”.

It goes on to say that NHS England will be holding two open events for patients to discuss the proposals and share feedback. The first event will be held in Leeds on Wednesday 22 August (12-2pm) and the second in London on Thursday 23 August (10am to 12pm). To register your interest, email: england.EBinterventions@nhs.net

It all seems sensible and who would disagree? Well, many professionals and patients will do – particularly those who view these attempts at “disinvestment” as rationing, primarily done to save money rather than improve care. Let us see what the backlash will be. The next day, on the morning of the NHS’s 70th birthday, I was interviewed by Ann Robinson, a GP and contributor to The Observer, writing for the BMJ on the issues.

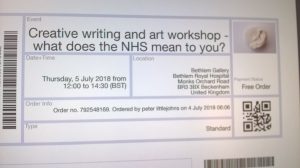

After finishing the interview, I set off to take part in the celebrations. I had approached the 70th anniversary celebrations with mixed feelings. It reminded me of a birthday of an aging, loved, but failing relative – how do you celebrate when there are serious concerns over their future wellbeing? As the CLAHRC has five NHS partners I was wondering where to go – in the end I went to the Bethlem Royal Hospital, part of the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. The hospital started life in 1247 as the Priory of the New Order of our Lady of Bethlehem. The word “bedlam” meaning uproar and confusion, is derived from the hospital’s prior nickname. Having moved sites a number of times in its 600-year history, it is now in the grounds of Monks Orchard House in Beckenham, south-east London.

Why the Bethlem hospital? Well, the day before I was reading a blog on the BMJ website by David Gilbert – a patient director from Sussex who is advocating a much more active role for patients in seeking to commission a sustainable health service.

His argument is that “We have a ‘patient-centred’ NHS being run by system leaders who are the managerial and clinical elite. It is akin to a ‘woman-centred’ organisation being run by men.” David’s thoughts resonated with what we are trying to achieve in our CLAHRC project – to encourage the public to be more actively involved in deciding what the NHS should provide and what it should not – which is proving challenging to implement. On the issue of local involvement, David suggests that “patients and the public have been excluded from senior decision-making roles in structures created around new ‘models’ of care design and delivery. This includes ‘sustainable transformation plans’. Subsequently, issues that should be discussed openly with patients and citizens as part of decision-making are happening behind closed doors. This includes issues like whether to spend money on ‘low priority procedures’”.

At the end of the blog he announced a creative workshop to celebrate the NHS in his capacity as writer-in-residence at the Bethlem hospital.

I decided to go to meet David and participate in his workshop as my involvement in the day’s celebrations. It was not exactly what I was expecting. Although publicly advertised, the majority of the ‘would be’ artisans were local patients. The workshop proved to be uplifting – what better way to celebrate the NHS’s anniversary then to hear directly from patients themselves what it means to them? We first heard David reading his own poems on his experiences as a patient and carer. We were then invited to give word associations of what we felt about the NHS. These were captured and mixed up and we had to take two unseen words and create a poem. Words like “hope” and “caring” were matched with “anger” and “disappointment”. We were joined by the artist-in-residence Beth Hopkins, who had created a three-dimensional depiction of the NHS. This and David’s poems were recorded in a booklet.

I left inspired, having celebrated the NHS in appropriate style, and with a future meeting planned with David to explore new ways of encouraging patient and public partnership in commissioning. However, a further email exchanged revealed that David was already viewing this new “sensible” NHS England stopping guidance as top down rationing and likely to portray patients as unreasonable, wanting wasteful treatments. I look forward to debating the need for this type of approach, but to learn how it can be achieved in an acceptable manner.

Implementation science must have something to say on this issue – it will be as much about understanding the role of public involvement and ethics as “change management” and health services research.

Leave a Reply