Daniel Buarque

PhD Candidate at the Joint PhD in International Relations – King’s College London and University of São Paulo.

Brazil aspires to a greater active involvement in international relations, to acquire a higher status, and to become recognised as an important player in the global arena. Two separate surveys conducted with the Brazilian foreign policy community show that at least 97% of the respondents favour a more active international role (1). Sources inside the Brazilian government are also unanimous in recognising the importance of the country’s image and prestige abroad (2). Status-seeking has been a dominant and constant factor in Brazil’s foreign policy. All Brazilian governments, since the country became independent in 1822, have shared a key aspiration to seek an influential global role for their country (3). Brazil believes it is entitled to this high-level status based on its perception of the traditional arguments of continental size, natural resources, and economic profile (4). Everything Brazil does in international politics is aligned with the objective of gaining recognition (5).

Ambitions of achieving global importance and international influence are, therefore, not new to Brazilian foreign policy. The drive for prestige as a constitutive element of power lies in the very formation of Brazil and has long been a part of the history of diplomatic relations within the country and is even considered part of the international identity of Brazil (6). Much of this identity comes from the work and legacy of the Baron of Rio Branco, as he inspired the style of diplomatic behaviour that characterizes Brazil (7).

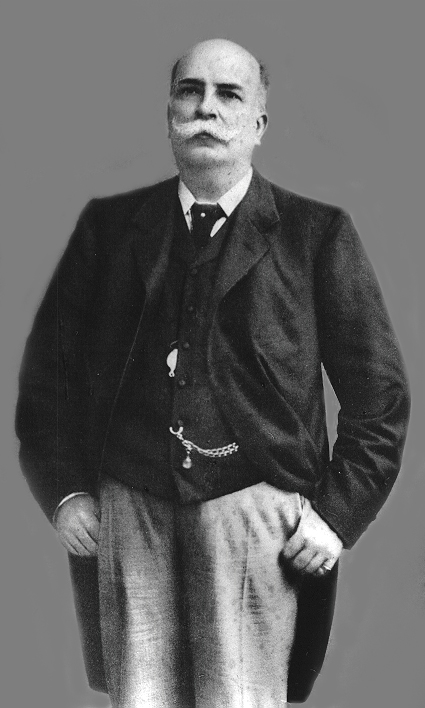

José Maria da Silva Paranhos Jr., the Baron of Rio Branco, was the Brazilian Minister of Foreign Relations from 1902 to 1912. When he died, his legacy involved the idea of Brazil as a peaceful nation, with defined national boundaries and a large territory. Diplomat, geographer, historian, monarchist, politician and professor, he has been described as one of the “founding fathers” of Brazilian nationality and of the diplomatic traditions of the country. He was, to a large extent, also responsible for the creation of the idea of Brazil, of the nation, and of the Brazilian nationality departing from a foreign policy perspective (8).

One of the very important pieces of the puzzle of national identity and diplomatic style developed by Rio Branco was this primacy of prestige and status among Brazil’s international agenda priorities. In the early 20th Century, Brazil was still, however, a very provincial nation that had little participation in international issues. This was seen as one of the reasons why Rio Branco worked to professionalise the Brazilian diplomacy and insert Brazil into a global context. The aim, to boost the level of the country’s participation in the international scene (9).

Brazil’s image abroad was a constant concern for the Baron, he wanted to cultivate a strong international image. This was a crucial element in the management of the country’s relations with the Great Powers of Europe. Gaining prestige on Brazil’s behalf was not, consequently, just a matter of vanity and pride, but part of a larger strategy to insert Brazil in the international system of that time (10).

In his very thorough biography of the Baron, Santos (2018) discusses how the importance of Brazil’s international image for the country was well established throughout the life of the Baron. The book also offers numerous examples of how Rio Branco often based his decisions as part of great attempts to project a positive image of Brazil.

In his diplomatic work and efforts to promote Brazil internationally, Rio Branco paid foreign periodicals to try and project a positive image of the country. He offered subsidies to London’s “South American Journal and Brazil and River Plate Mail” as well as Paris’ “Le Brésil”. The Brazilian Chancellor organized an information service to send the international press news from Brazil which could interest the foreign public. This shows that Rio Branco had an early understanding of what would later be known as public diplomacy, helping to modernise the work of Itamaraty (the Brazilian Foreign Ministry). (10)

Rio Branco made the search for international prestige a part of the implementation of Brazilian diplomacy. In one example of this, he instructed the Brazilian jurist, Rui Barbosa, in his work representing Brazil in the Second Peace Conference of Hague in 1907. The main contribution of this partnership was in defence of equality between states and a rejection of a different treatment to nations at the summit based solely on their material power, which the two saw as a discriminatory measure (9). Although the country has appeared to many in the press and international political circles as responsible for the failure of the Hague Conference, Brazil’s performance in the summit did contribute to increasing its international projection (10).

Considering the issue of Brazilian image abroad to be crucial, Rio Branco transformed the Itamaraty Palace in Rio de Janeiro into a mandatory stop for personalities of international expression who passed through Brazil. Due to this, the Baron defended the need to modernise, clean and embellish the national capital. This would lead the city to host international events and visitors and contribute to changing the image of instability that had marked the first years of the Republic and instead promote an image of a modern, stable and urban nation (10).

Another important area viewed by the Baron as significant to increase Brazil’s prestige was his interest in ending slavery. Though it was recognised as a crucial issue in domestic politics, it also had noteworthy effects abroad on the matter of Brazil’s international image. For this reason, Rio Branco argued it was important to publicise the reforms in Europe, showing that it marked the end of slavery in the so-called civilized world. This was a way in which Rio Branco tried to show that Brazil was in fact civilised and to try and leave behind the stain of slavery that was fixed to the image of the country abroad (10).

Although it is not entirely clear as to what caused this preoccupation of the Baron’s regarding the image of his country, Santos’ biography offers an anecdote that can be seen as causing what would later be known in the country, called by Nelson Rodrigues the “complexo de vira-latas”, the mongrel complex: the position of inferiority in which the Brazilian voluntarily puts himself in face of the rest of the world (11) .

While spending time in Paris in his youth before becoming the Baron, the young Paranhos Jr. watched Jacques Offenbach’s operetta “La Vie Parisienne” at the Théâtre du Palais-Royal, which showed a specific depiction of his nationality that would make him uncomfortable with the image of Brazil abroad. One of the characters included in the plot, “the Brazilian”, was a sympathetic nouveau-riche with bad manners and bad taste, as well as being spendthrift, naive and given to ostentation. In his introduction, “the Brazilian” explained that he came from Rio de Janeiro loaded with gold in his luggage and with diamonds on his shirt. In his previous visits to the city, he had stayed long enough to make two hundred friends and win four or five lovers in six months of love intoxication. He had enjoyed life well until Paris took all the money he had brought with him. And yet, “the Brazilian” returned, excited (10).

According to Santos (2018), this caricature reflected the image of Brazil that was being created in certain European circles. This bothered Rio Branco. “The caricature hurt the feeling of identity with the civilization to which Brazilian elites thought they belonged. If the Brazilian monarchy thought of itself as European, there was no reciprocity. The Old Continent saw Brazil in a way that was closer to reality: a backward country, with great natural wealth, run by an elite not very fond of work”, according to Santos (10).

This early contact by the Baron with such a negative depiction of his nation can be interpreted as one of the origins of the “status anxiety” that would permeate Brazil’s relations with the rest of the world for more than a century. This anxiety refers to the idea that one’s self-conception is dependent upon what others think about them. The negative connotation in this external view can lead to a permanent worry of not conforming to ideals of success and the risk of being stripped of dignity and respect as well as an awareness of the need to convince the world of one’s value (12). The impression left in Rio Branco must have been a painful one, and the country’s image abroad would become one of the Baron’s great concerns in the performance of his diplomatic functions and in the head of the Chancellery (10).

References:

(1) Souza, A. de (2002) A Agenda Internacional do Brasil: Um Estudo sobre a Comunidade Brasileira de Política Externa. Rio de Janeiro: CEBRI. — Souza, A. de (2008) Brazil’s International Agenda Revisited: Perceptions of the Brazilian Foreign Policy Community. Rio de Janeiro: CEBRI.

(2) Moura, L. C. (2013) A Marca Brasil: O Poder da Imagem e a Construção da Identidade Competitiva. Brasília: Instituto Rio Branco/Ministério das Relações Exteriores. — Nogueira, S. G. & Burity, C. (2014) A construção da imagem do Brasil no exterior e a diplomacia midiática no governo Lula. Revista de Ciências Sociais. (41), 375–397.

(3) Mares, D. R. & Trinkunas, H. A. (2016) Aspirational power: Brazil on the long road to global influence. Geopolitics in the 21st century. Washington, D.C: Brookings Institution Press. — Carvalho, B. de (2020) ‘Brazil’s (Frustrated) Quest for Higher Status’, in Status and the Rise of Brazil. Springer. pp. 19–30. — Carvalho, B. de et al. (2020) ‘Introduction: Brazil’s Humanitarian Engagement and International Status’, in Status and the Rise of Brazil. Springer. pp. 1–15. — Casarões, G. (2020) ‘Leaving the Club Without Slamming the Door: Brazil’s Return to Middle-Power Status’, in Status and the Rise of Brazil. Springer. pp. 89–110. — Stolte, C. (2015) Brazil’s Africa Strategy. [Online]. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. [online]. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1057/9781137499578 (Accessed 7 February 2018).

(4) Larson, D. W. & Shevchenko, A. (2014) ‘Managing rising powers: The role of status concerns’, in Status in world politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 33–57. — Hurrell, A. (2006) Hegemony, liberalism and global order: what space for would‐be great powers? International affairs. 82 (1), 1–19. — Fonseca, C. (2017) O Brasil de Lula – A permanente procura de um lugar no sistema internacional. Relações Internacionais. 5551–70.

(5) Burges, S. (2013) Mistaking Brazil for a Middle Power. Journal of Iberian and Latin American Research. [Online] 19 (2), 286–302.

(6) Lafer, C. (2001) A identidade internacional do Brasil e a política externa brasileira: passado, presente e futuro. Editora Perspectiva. — Ricupero, R. (2017) A diplomacia na construção do Brasil 1750-2016. Rio de Janeiro: Versal.

(7) Lafer, C. (2000) Brazilian international identity and foreign policy: Past, present, and future. Daedalus. 129 (2), 207–238. — Malamud, A. (2011) A Leader Without Followers? The Growing Divergence Between the Regional and Global Performance of Brazilian Foreign Policy. Latin American Politics and Society. [Online] 53 (03), 1–24. — Cervo, A. L. & Bueno, C. (2002) História da política exterior do Brasil.

(8) Santos, L. C. V. G. (2018) Juca Paranhos, o Barão do Rio Branco. Editora Companhia das Letras. — Santos, L. C. V. G. (2010) O dia em que adiaram o Carnaval: política externa ea construção do Brasil. Editora UNESP. — Burns, E. B. (1967) Tradition and Variation in Brazilian Foreign Policy. Journal of Inter-American Studies. [Online] 9 (2), 195–212. —Lafer, C. (2009) ‘Brazil and the World’, in Brazil: A Century of Change. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 101–120. — Lafer, C. (1990) Reflexões sobre a inserção do Brasil no contexto internacional. Contexto Internacional. 11 (1), 33.

(9) Cardim, C. H. (2007) A Raiz Das Coisas-Rui Barbosa: O Brasil No Mundo. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira.

(10) Santos, L. C. V. G. (2018) Juca Paranhos, o Barão do Rio Branco. Companhia das Letras

(11) Rodrigues, N. (1993) À sombra das chuteiras imortais. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

(12) De Botton, A. (2008) Status anxiety. Vintage.