Raphael C. Lima, PhD candidate in War Studies at King’s College London

Peterson F. Silva, Professor at the Brazilian War College (Escola Superior de Guerra, Ministry of Defence)

Gunther Rudzit, Associate Professor of International Relations at ESPM and Professor at the Brazilian Air Force University (UNIFA)

Making sense of the security apparatus in contemporary Brazil is a complex issue. Nowadays, people may find snapshots of Brazilian security agencies’ actions through the news. Examples are varied: armed bank robbers violently storming small Brazilian cities; civilians killed by ‘stray bullets’; Brazilian Armed Forces fighting environmental crimes in the Amazon region; Brazilian institutions hit by cyberattacks; the Federal Police’s constant operations against money laundry and political corruption; Armed Forces repressing border crimes; militias expanding control in Rio de Janeiro; and police officers killing and being killed on Brazilian streets. But why do we need to analyse and understand roles, missions and coordination between different security agencies?

Organising security forces is a necessary challenge for contemporary democracies. After all, a failure to define specific roles to security forces and not providing them with effective resources and limits can lead to grave social problems, human rights violations, inefficient use of resources, and ineffective use of force. This is especially important in the contemporary world. The nature of security threats has gone beyond traditional state-to-states and demands larger cooperation and integration among military branches, police forces, gendarmery forces, and intelligence services. Providing political direction and management of these issues is what the literature calls national security policymaking. That is, ‘the process of maintaining, coordinating and employing the assets of the security sector so that they contribute optimally to the nation’s strategic goals’ (Chuter 2011, p.13).

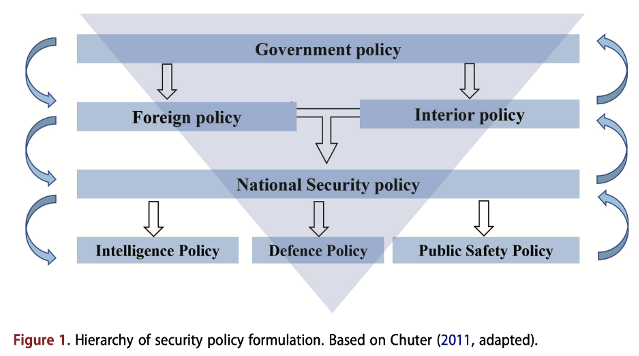

This national security policymaking activity coordinates and gives a larger common direction to three main axes of a state’s national security policy: intelligence, defence, and public safety (Figure 1). This is a process of policy engineering that can be comprised of two main elements. First, national security documents—a National Security Policy or Strategy (e.g., France, U.S., Spain and UK strategies)—capable of providing general guidelines for the whole security apparatus. However, only having a strategy is not enough. There must also be effective national security institutions who are responsible for putting together strategies and directions for the whole security sector (e.g., the U.S. and the UK National Security Councils, and France Stratégie). That is, cross-sector permanent organisations with permanent specialised civilian personnel that can coordinate and provide major guidelines. Once these are put in place, then, this larger policy instructs the three main axes of a national security policy, defence, intelligence, and public safety.

Understanding this complex mosaic of security agencies and missions may seem complex in a Brazilian contemporary environment. Especially in a domestic security environment with high levels of social violence—violent death rate of 27.5 per 100,000, rising paramilitary groups in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, and organised criminal organisations, such as the First Capital Command (Primeiro Comando da Capital—PCC) and the Red Command (Comando Vermelho—CV), going global and operating in Paraguay, Bolivia and Peru. Nowadays, these issues have become more complicated by the Venezuelan crisis that has spurred global geopolitical competition between the U.S., China, and Russia in Brazil’s vicinity. South America is no longer a region distant from great power politics and thus military diplomacy and capabilities become important resources.

However, Brazil lacks a clear and structured national security strategy or clear cross-sector definitions. Quite the opposite, one may see more and more military officers acting in defence and intelligence leadership positions without the presence of institutionalised civilian roles; a military expenditure characterized by approximately 79% assigned to Personnel costs and 13% to Equipment in 2019; bureaucratic struggles between military service branches; fragile controls and oversight mechanisms in defence, intelligence, and public safety; and growing examples of Armed Forces deployed in public safety.

Not having effective national security policymaking may have negative effects on security policies. In the case of post-authoritarian states, traditional problems of civil-military relations—such a democratic controls over the armed forces, civilianisation of the defence sector, creating effective political directions, engaging society and the parliament in security and defence topics—might be worsened when internal security threats rise. This seems to be the case of Brazil. What is the effect of not having civilianised and effective national security policymaking to the defence sector in the country? What is the relationship between fragile coordination among security agencies, weak democratic controls, and the growing military engagement in public safety? Our recent article published in the journal Defence Studies aimed to address this question.

We argued that, since democratisation in 1985, civilian elites have neglected national security policymaking and the military has since maintained several military prerogatives. Instead, as internal security challenges grew in complexity, civilian political elites pushed the military to deal with public safety, border security, and national security policymaking. The military, in turn, resisted defence reforms that challenged their prerogatives. Additionally, political elites delegated civilian posts to the Armed Forces in defence, public safety and intelligence, instead of engaging in broader reforms.

Our study shows that this led to a vicious cycle of military dependency, which deteriorated the already fragile political controls over the Armed Forces, inhibited defence reforms, and increased the military role in the state and society. This ultimately led to the resurgence of the military in the political arena. To reach this conclusion, we analysed the three axes of a national security policy—intelligence, public safety, and defence.

We noted that Brazil has had an un-concluded national security policymaking process. The larger cross-national coordination process at the Federal level has never come to fruition and did not move beyond specific ad hoc efforts, such as the Strategic Border Plans, and the security coordination during the international events held in the country. Regarding the Intelligence sector, Brazil did build a civilian agency, the Brazilian Intelligence Agency (ABIN), in 1999. Yet, ABIN has been subject to military gatekeeping since it is directly subordinate to the Institutional Security Cabinet (GSI/PR), a Ministry-level organisation led by Army Generals since 1985 and that does not have to be approved by Senate hearings. The public safety area has also contributed to this in process. In general, Brazilian police forces have a low law enforcement capacity and are very fragmented. Corruption, lack of basic supplies and equipment for policing activities, low effectiveness, and police strikes are very common problems.

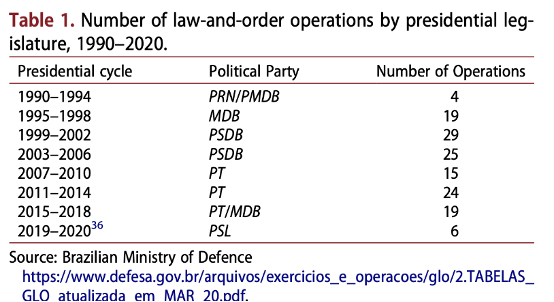

Instead of broader reforms and coordination, civilians aimed to solve these crises by slowly pushing the military to deal with internal security problems. From border crime repression to temporary domestic deployments to guarantee law and order (GLO operations)—that grew in time and scope over time (table 1)—, the Armed Forces have been expanding their involvement in internal affairs. These new missions and domestic military deployments have affected the results of defence reforms. In general, civilians did not engage on broad reforms that tacked military prerogatives and most reforms put forward were those that favoured previous military agendas. As a result, the military maintained large political spaces for the armed forces within defence policymaking such as publishing the new defence strategies, defining budget priorities, occupying key ministerial posts etc. A key example is that the position of Minister of Defence has been occupied by Retired Army Generals since 2016.

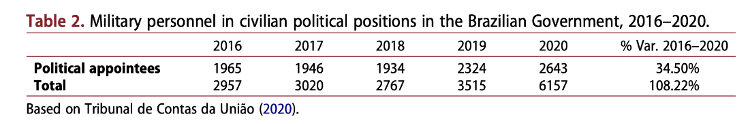

Over time, the combination of expanded roles in public safety and ineffective reforms inhibited defence reforms that have challenged military prerogatives—e.g., civilian careers in the Ministry of Defence or reducing the powers of the Military Commanders. As we argue, there is no power vacuum. As civilians neglected national security policymaking and delegated more and more posts to military officers in public safety and defence, the military expanded their role in these areas and occupied spaces. This ultimately led to the weakening of the already fragile democratic controls (table 2).

This, of course, is not a process set in stone and can be overcome. We consider that Brazilian civilian elites can move beyond this national security neglect and engage on proper national security policymaking. A few important first steps would be (1) to publish an effective national security strategy; (2) to create civilianised and institutionalised national security council/committee capable of providing political direction to security policies and coordinating cross-sectorial efforts; and (3) to create permanent civilian positions to the Minister of Defence and aim to improve military effectiveness; (4) to increase democratic controls of the defence sector, engaging parliament and other government agencies. Together these can be important initial steps to make sense of the security apparatus and start organising roles and missions between different security agencies.

References:

Chuter, D. 2011. Governing & Managing the Defence Sector. Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies.

Tribunal de Contas da União. 2020. Memorando N. 57/2020-Segecex. Brasília: Tribunal de Contas da União.

More details:

No power vacuum: national security neglect and the defence sector in Brazil

Defence Studies

Raphael C. Lima , Peterson F. Silva & Gunther Rudzit (2020)

DOI: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14702436.2020.1848425

It seems that to a certain extent the authors had a lack of comprehension on national security basic concepts, misunderstood with public safety. It’s actually the core of the debate when discussing its main issues.

You really need to read this paper carefully…