by Lucy Munro, Reader in Early Modern English Literature at the Department of English, and Emma Whipday, Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at UCL

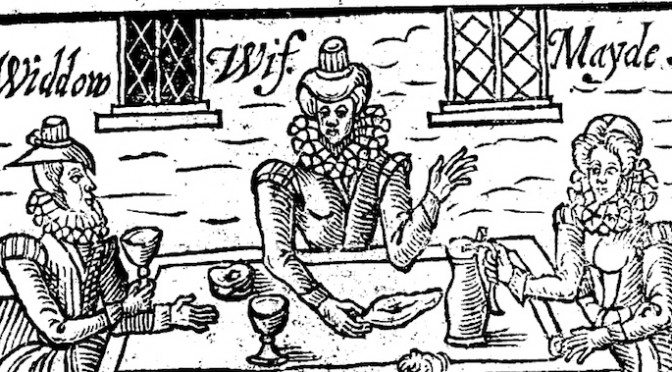

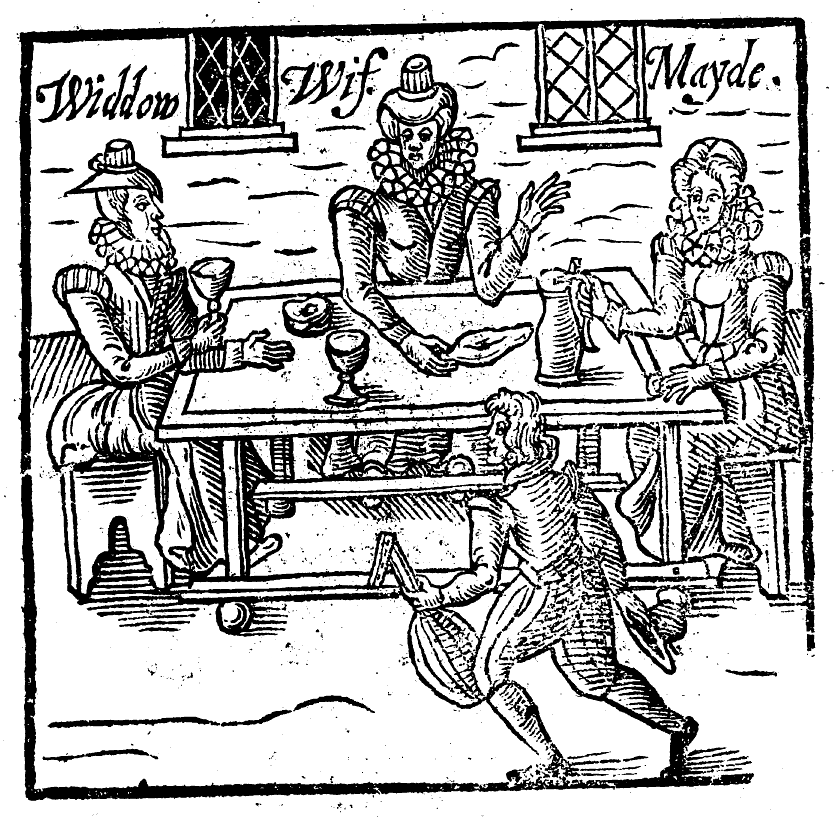

In 1624, a play entitled The Late Murder in Whitechapel, or Keep the Widow Waking was staged at the Red Bull playhouse in Clerkenwell. Written by Thomas Dekker, John Ford, William Rowley and John Webster, it was based on accounts of two recent crimes. The first was the murder of a Whitechapel woman, Joan Tindall, by her son, Nathaniel, which became the subject of at least two ballads, one of which survives. The second was the forced marriage of a 62-year-old widow, Anne Elsdon, to a much younger man, Tobias Audley.

Tobias lured Anne to a tavern, where he plied her with alcohol and tried to persuade her to promise to marry him – a promise that could be legally binding if it was said before witnesses. After several days he eventually seems to have got some kind of agreement from her, and a priest hired for the purpose married them. However, the ‘marriage’ became the subject of a series of cases in the secular and religious courts.

The Late Murder in Whitechapel, or Keep the Widow Waking was an early modern answer to what we now often call ‘verbatim theatre’ – performance pieces based on real-life events that draw on documentary and oral sources, including the testimony of participants and witnesses involved in those events.

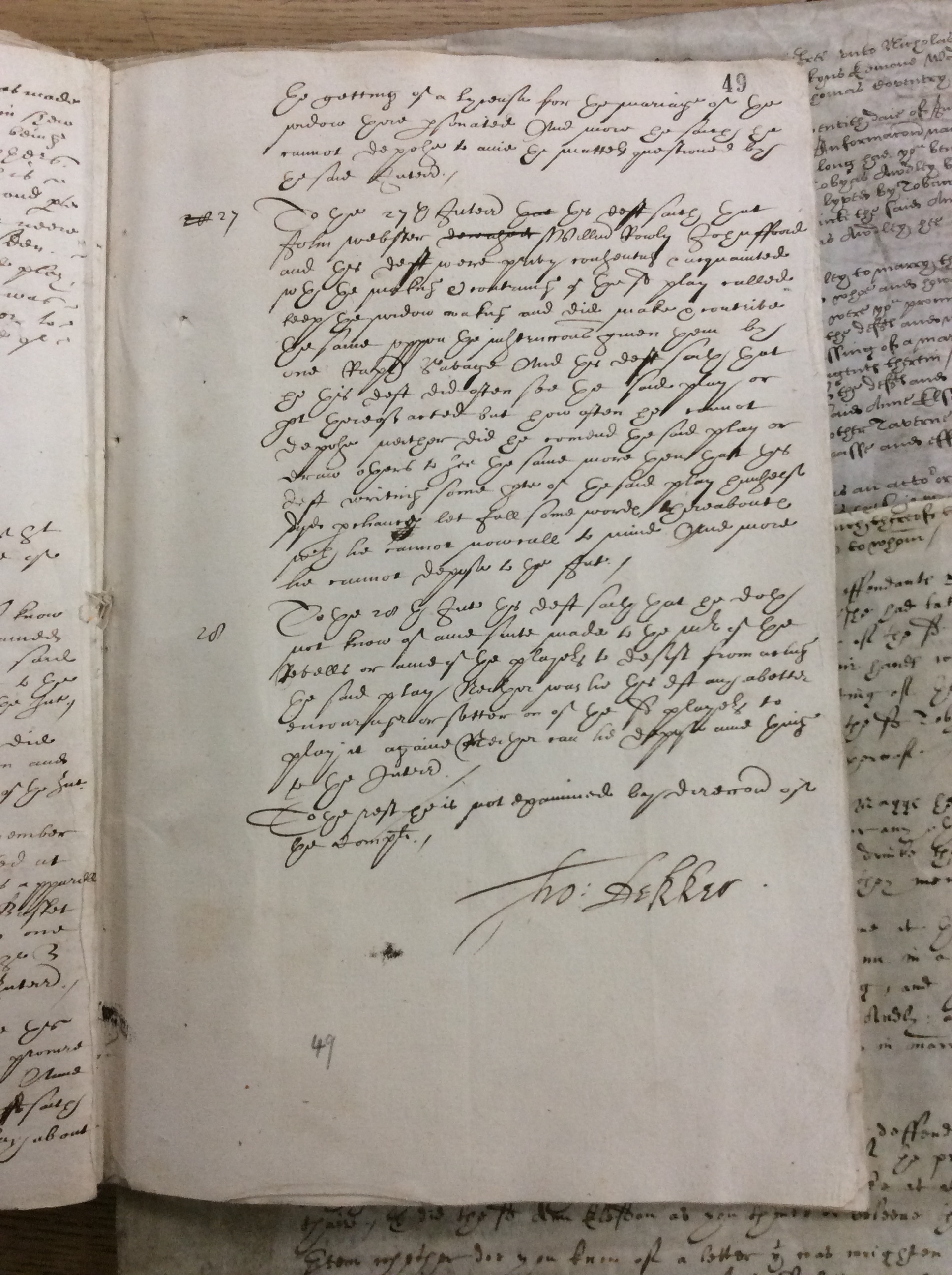

The playwrights seem to have drawn directly on oral testimony from one of the lawsuits, and their play was then cited in another suit. The play is now lost – a full account of what we know about it can be found in the splendid Lost Plays Database. However, documents from some of the lawsuits survive. One of them provides information about the play and reproduces the lyric of a ballad that was said to have been sung near the playhouse and Anne Elsden’s own house. It professes to offer advice to ‘You young men who would marry well’ and concludes with the lines:

And you who faine would hear the full

Discourse of this match-making,

The play will teach you at the bull,

To keepe the widow waking.

We don’t know how sympathetic the play was to Anne, but the ballad that advertised it is very much on the side of the young man who exploited her.

Twentieth- and twenty-first-century verbatim theatre has occasionally drawn on early modern materials – one example is The Staffordshire Rebels, performed at the Victoria Theatre in Stoke-on-Trent in 1965, which was one of the theatre’s early experiments with what artistic director Peter Cheeseman called ‘documentaries’. More recently, academic researchers such as Laura Gowing, Eva Griffith and Emma Whipday have begun to explore what might happen if extracts from early modern legal documents are put on their feet.

Our event in May this year brought together a group of verbatim theatre practitioners, actors, historians and theatre scholars, focusing on the Anne Elsdon case as both the subject of an early modern verbatim drama in 1624 and the potential source for a new ‘early modern’ verbatim piece in 2017.

The symposium began with two talks from academic researchers. Laura Gowing explored the Anne Elsdon case itself, drawing attention to her discovery of Anne’s own testimony before the church courts, which gives us the widow’s perspective on her criminal mistreatment. Lucy Munro’s talk encapsulated the aims of the symposium as a whole, looking at what we know of the dramatists’ approach to the Elsdon case and other documentary sources, and comparing their techniques with those of Cheeseman and his company in The Staffordshire Rebels, giving a glimpse of how contemporary theatre can engage with early modern records.

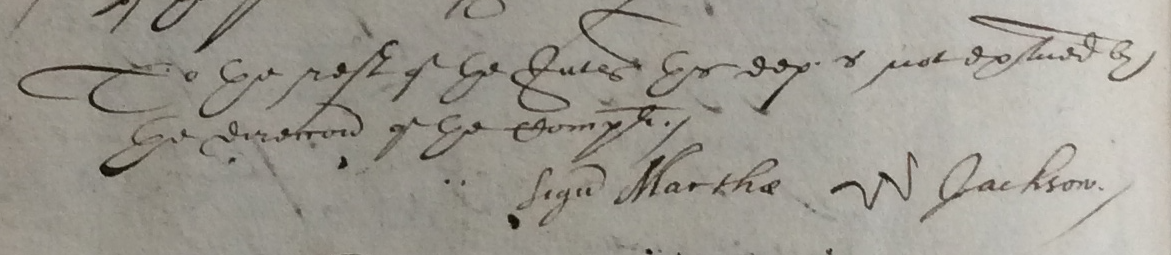

![The deposition of John Snowe in one of the lawsuits over the marriage of Anne Elsden and Tobias Audley, one of the documents on which our symposium and workshop scenes drew. The National Archives, STAC 8/13/16 [link: http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C5568370]. We are very grateful to Lauren Cantos, Kim Gilchrist, Jennifer Hardy, Suzanne Lawrence, Miranda Fay Thomas and Jennifer Young for helping us to prepare transcriptions of the lawsuits](https://blogs.kcl.ac.uk/english/wp-content/blogs.dir/141/files/2017/07/scribbly-manuscript-e1500967009480.jpeg)

Engaging young people in care, building a community, exploring restorative justice and responding to violence – the ways in which verbatim theatre can be used…

These talks were followed by a practitioner roundtable. Maggie Inchley (Queen Mary, University of London) and Sylvan Baker (Central), discussed their project ‘The Verbatim Formula’, which uses theatrical practice to engage with young people in care, involving young people in the theatrical process of telling their stories. Ben Hadley (On the Button Theatre) shared details of the variety of ways in which his company On the Button uses (and re-imagines) verbatim accounts, and suggested the significance of verbatim theatre as a way of building a community. Harriet Madeley (author of verbatim piece The Listening Room) discussed how The Listening Room explores restorative justice, and described the process of using verbatim interviews to stimulate conversations about responses to violence. All participants explored the ethics of working from verbatim records, and talked about their different ways of involving interview subjects in the creative process.

We were then joined by four actors – Virginia Denham, Andrew Murton, Simona Bitmate and George Johnston – to workshop two different ‘scenes’ drawing on verbatim accounts from the transcribed Elsden court records, written by Harriet Madeley and Emma Whipday. Harriet focused on the initial attempted courtship of Anne by Tobias, staging Tobias’s accounts of his own motives and actions, and playing with the very different account of this courtship by Anne’s friend Martha Jackson, which exposes Tobias’s lies; it also used the ballad – sung together by the audience – to devastating effect. Emma’s scene explored the diverse voices involved in the case, from the man who purchased powders from an apothecary to drug Anne Elsdon, to the neighbour who shut her window to drown out Anne’s cries; it ended with Anne’s newly discovered testimony.

Workshopping these scenes enabled us to explore the richness of the case, and to experiment with how creative practice could help us to engage with the records from a theatrical perspective.

It would be impossible to recreate the Keep the Widow Waking of Dekker, Ford, Rowley and Webster, but this event enabled us to explore how archival materials and theatrical practice, theatre historians and theatre practitioners, can speak to one another – and how an encounter between these disciplines can enrich both.

___________________________________________________________________________

You may also like to read

Shakespeare 2.0: Pray tell, what is a ‘Mooc’?

‘A New Route Discovered’: On Shakespeare’s Sonnets

King’s Shakespeare Festival: What You Will

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and neither those of the English Department, nor of King’s College London.