by Carleigh Morgan, PhD Candidate in English Research, Christine Okoth, LAHP funded PhD candidate in Contemporary American Literature, and Bryony White, LAHP funded PhD candidate in Performance Studies

In response to the results of the US presidential election, staff and students of the King’s English Department hosted a Trump Teach-In on 23rd November 2016. The workshop consisted of brief talks and activities, many of which were student-led and all of which offered a multitude of different perspectives on an event that will have lasting global repercussions.

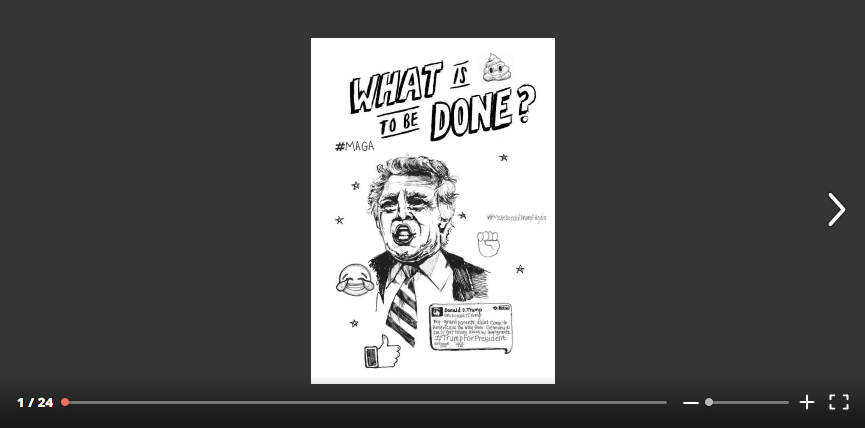

As research students in the department, we wanted our contribution to engage creatively and discursively with the politics of reaction and to be staged as a collaborative art project, one that underscores how the performances of reaction, the expression of feeling, and the policing of “permissible” behaviours are all aspects of the political (thought of here as a set of orientations and practices rather than static political frameworks or ideologies). We invoked Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s question ‘What is to be Done?’ from the title of her 2011 presidential address to the American Studies Association: her title itself performs a direct appropriation of Vladimir Lenin’s controversial political pamphlet from 1902 of the same name.

This central question: “What is to be Done?” identifies a starting point for thinking about how reactions, discussion, and debate can be channelled into action – action, in this case, as the documentation of a reaction at a decisive historical moment. Written during the Iraq war, Gilmore’s speech repeatedly broaches the problem of the intellectual and often distant nature of academic work and its relationship with and responsibilities towards the world outside.

In light of how disruptive the events of early November felt to many members of King’s, our activity was intended as a reminder that political currents are not an anomaly but the result of a historical genealogy. More importantly, we wanted to explore practical ways that students and researchers can be responsive to the ways that profound and globally transformative events impact their staff and student populations.

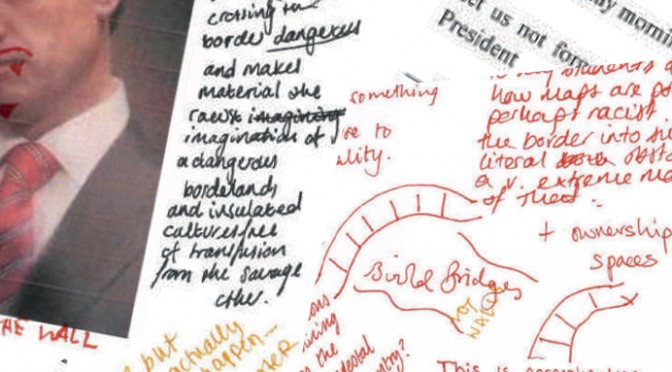

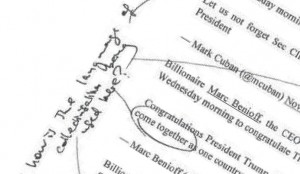

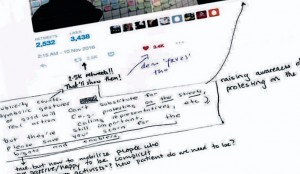

The flurry of individual social media users, voters, and pundits sharing their reactions to announcement of Trump’s election online contributed to the event as a political spectacle of reaction – reactions that continue to bring competing narratives and perspectives into the folds of the media-state nexus. For the duration of the teach-in we asked attendees to respond, scrawl, draw, and annotate a sample of images and writing produced during the election process. We chose a variety of responses that reflected a spectrum of attitudes, beliefs and ideologies. The materials we circulated consisted of pictures, memes, articles from ‘alt-right’ outlets, liberal blog posts, and visual art. The results of the project are presented within a zine, which we circulated in print on campus, and is available to view below.

It was important for us to engineer the output of this exercise as a zine: a format that is historically associated with punk movements, protest, and abject art that is designed to elicit polarizing response. We approached this task without assuming the opinions of the student body as a general demographic, and hoped that students would respond in an open-ended way to the materials that we circulated to them.

Historically, the form of the zine has been associated with resistant politics. We hope that this zine will serve as an unfolding reminder and intervention into the events of the recent US presidential election. Furthermore, we hope that it will provide a method through which to engage with recent events, whilst offering an alternative model of resistance – playful or otherwise – for its readers.

Detail images and embedded link to Issuu copy of ‘What is to be Done?’ zine.

You might also like to read People and Poems at Political Demos

Blog posts on King’s English represent the views of the individual authors and not those of the English Department, nor King’s College London.