By Frances Carey, Visiting Senior Research Fellow, English Department, and co-curator of Painting Norway. Nikolai Astrup 1880-1928, Dulwich Picture Gallery 5 February to 15 May 2016.

An elephant’s gestation is ‘but as yesterday when it is past, and as a watch in the night’ compared with that required for most museum exhibitions. The one just opened at Dulwich Picture Gallery was not even a twinkle in anyone’s eye at the seminar I was invited to join four years ago in Bergen, to consider how to raise the international profile of Nikolai Astrup.

Though cherished in Norway he is pretty well unknown elsewhere, a good example of how becoming a ‘national treasure’ can hinder wider recognition. Scarcely a work of his exists outside Norway and none whatsoever in any public collection abroad. Within Norway many of Astrup’s paintings and prints have never come onto the market, remaining with the families of those who obtained them direct from the artist or through a close intermediary. But in 2005 the Savings Bank Foundation DNB acquired the most important private collection of Astrup’s work, placing it on long-term loan to KODE Art Museums of Bergen. This had to be the starting point for our discussion, and it has provided the core of the exhibition.

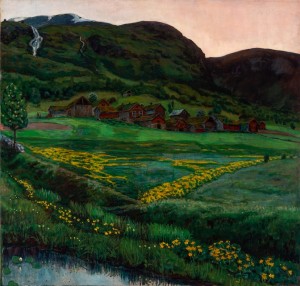

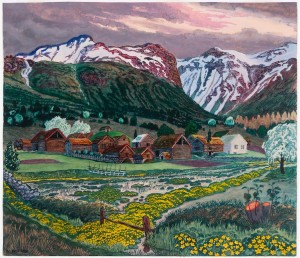

Why should a ‘faraway artist of whom we know little’ be of interest to the rest of the world? The eureka moment came in June 2012 when the ‘seminar’ was taken to Jølster in western Norway – four hours by road and ferry from Bergen – a lakeside region surrounded by mountains where Astrup lived for the greater part of his short life. The sun shone unstintingly – a rare feat since western Norway has one of the highest rates of rainfall – as we were taken into a  landscape of surpassing beauty and grandeur. Immediately his work came to life, not as an exact topographical record but as a distillation of the childhood memories that were the mainspring of his creativity. His fear of ‘profaning’ these ‘inner pictures’ as he called them, with other sights, scenes and experiences, brought him back to Jølster in 1902 after a period of study in Kristiania (Oslo) and Paris, travelling via Germany. He returned to ‘wash’ himself ‘in the raw colours of Western Norway in order to cleanse myself of everything that I may have ingested from the art of others in order to escape from all influences and to arrive at my own [style]..’

landscape of surpassing beauty and grandeur. Immediately his work came to life, not as an exact topographical record but as a distillation of the childhood memories that were the mainspring of his creativity. His fear of ‘profaning’ these ‘inner pictures’ as he called them, with other sights, scenes and experiences, brought him back to Jølster in 1902 after a period of study in Kristiania (Oslo) and Paris, travelling via Germany. He returned to ‘wash’ himself ‘in the raw colours of Western Norway in order to cleanse myself of everything that I may have ingested from the art of others in order to escape from all influences and to arrive at my own [style]..’

Jølster has changed little from Astrup’s lifetime. The church at Ålhus where Astrup’s father was the Lutheran pastor and where Astrup is buried, remains as it was; a portion survives of the parsonage, his parental home, where he lived, bar brief periods away, from 1883-1911; the hotel at Skei, the main settlement further along the lake, is a modern building, but a substantial tourist hotel has been there since 1889; above all in every sense of the phrase, lies the steeply terraced plot of land on the south side of the lake with its cluster of turf-roofed wood cabins, where Astrup made his own family home from 1913 onwards. At Sandalstrand he, then his young widow Engel, created a kind of rural gesamtkunstwerk combining practical self-sufficiency with ‘artistic’ landscaping, planting and pruning outdoors, and ‘interior still-lifes’ within, composed from traditional wooden furniture, Astrup’s paintings, potted plants, ceramics and textiles woven and printed by Engel. In 1965 she sold Astruptunet as it is now known, to the local municipality which has opened it to the public in the summer months since 1986.

The ‘lived experience’ of this visit was crucial to the momentum of formulating a proposal that Ian Dejardin, the Sackler Director of Dulwich Picture Gallery, took to his Board of Trustees early in 2013, and to the subsequent negotiations with lenders, venues, publisher, press and many other constituents besides. The ‘A’ team was quickly formed, headed by Ian Dejardin, MaryAnne Stevens (formerly Director of Academic Affairs at the Royal Academy) and myself as the principal curators, aided by two Norwegian colleagues, one in Bergen and the other in Oslo -Tove Kårstad Haugsbø and Kari Greve – John Myerscough, a cultural consultant working on Astruptunet, Eric Pearson the designer, and Rebecca England the project manager at Dulwich. We were hugely helped by factors that are often hard won but in this case were forthcoming from the outset: a generous, engaged sponsor, access to private collections for work little seen even within Norway and never outside, and a considerable repository of archival material and expertise.

The ‘lived experience’ of this visit was crucial to the momentum of formulating a proposal that Ian Dejardin, the Sackler Director of Dulwich Picture Gallery, took to his Board of Trustees early in 2013, and to the subsequent negotiations with lenders, venues, publisher, press and many other constituents besides. The ‘A’ team was quickly formed, headed by Ian Dejardin, MaryAnne Stevens (formerly Director of Academic Affairs at the Royal Academy) and myself as the principal curators, aided by two Norwegian colleagues, one in Bergen and the other in Oslo -Tove Kårstad Haugsbø and Kari Greve – John Myerscough, a cultural consultant working on Astruptunet, Eric Pearson the designer, and Rebecca England the project manager at Dulwich. We were hugely helped by factors that are often hard won but in this case were forthcoming from the outset: a generous, engaged sponsor, access to private collections for work little seen even within Norway and never outside, and a considerable repository of archival material and expertise.

Astrup is a wonderful writer whose every note and letter is revealing of his intense inner life, a daily struggle with himself as much as with often very adverse external circumstances. Marvellous descriptive passages evoke the sensations – visual, musical, psychological and physiological – that the landscape produced in him. The repetition of motifs – a marked feature of his work – is never about uniformity but about capturing different moods conveyed through changing weather, light, colour and medium. Printmaking, especially in woodcut, was every bit as important as painting, indeed the two were completely integral to each other.

Astrup’s landscape is a landscape of the mind made manifest through the artist’s skill as a painter and colourist.

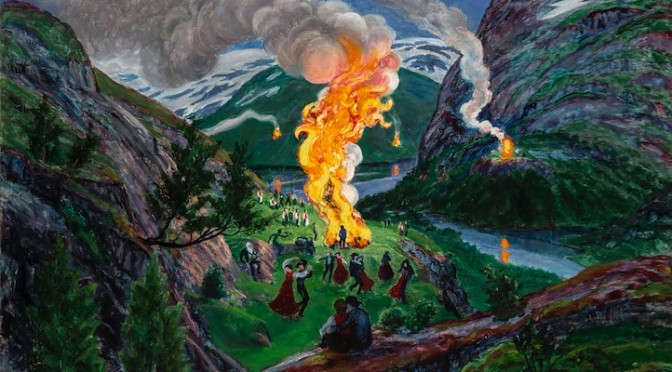

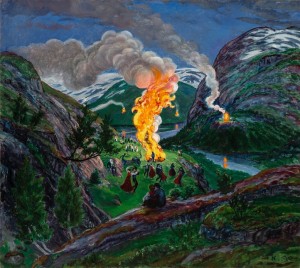

It is always difficult to bring the outside world in, but that is what we wanted to achieve at Dulwich. Astrup’s subjects range from the domestic environs of home and garden, the changing aspects of the lake in early spring, and an undulating line of mountain peaks transformed into a naked reclining ‘Ice Queen’ seen through the branches of a ‘troll tree’, to a yellow carpet of marsh marigolds among the ‘smiles of a summer night’ in June. The crowning glory of the seasonal year, as well as the exhibition, is Midsummer’s celebration. Astrup’s depictions almost literally smoulder with bonfires, dramatic effects of light and shadow, and the suggestion of sexual desire amid the revelry from which he was barred in his youth by his stern God-fearing father.

Frances Carey is Senior Visiting Research Fellow in King’s English Department and teaches on the MA in 18th-century studies. She is a consultant curator and advisor to arts and heritage organisations, and formerly Senior Consultant for Public Engagement at the British Museum, where she also held the positions of Head of National Programmes and Deputy Keeper of Prints and Drawings.

Painting Norway. Nikolai Astrup 1880-1928, Dulwich Picture Gallery 5 February to 15 May 2016 then at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter, Høvikodden, Norway 10 June to 11 September 2016, and Kunsthalle Emden, Germany, 1 October 2016 to 22 January 2017. Supported by The Savings Bank Foundation DNB. Accompanying catalogue by Frances Carey, Ian A.C. Dejardin and MaryAnne Stevens with contributions by Kari Greve, Tove Kårstad Haugsbø and John Myerscough, Scala Arts and Heritage Publishers Ltd in association with Dulwich Picture Gallery, London 2016

Image Credits:

Featured: Nikolai Astrup, Midsummer Eve Bonfire, After c.1917, Oil on canvas, 60 x 66 cm The Savings Bank Foundation DNB/The Astrup Collection/KODE Art Museums of Bergen

Figure 1: Nikolai Astrup, A Clear Night in June, 1905- 1907, Oil on canvas,148 x 152 cm, The Savings Bank Foundation DNB/The Astrup Collection/KODE Art Museums of Bergen. Photo © Dag Fosse/KODE

Figure 2: Nikolai Astrup, Marsh Marigold Night, c.1915, Colour woodcut on paper, 40.7 x 47 cm, The Savings Bank Foundation DNB/The Astrup Collection/KODE Art Museums of Bergen. Photo © Dag Fosse/KODE