Part II of Professor Peter Littlejohn’s reports from Australia and New Zealand…

My first port of call in New Zealand was on the South Island to meet my CLAHRC-project collaborators. Dunedin is Gaelic for Edinburgh and the city was founded in 1848 by a small group of Scottish emigrants. Remarkably, just 23 years later the University of Otago was opened on 5 July 1871 – the first University in New Zealand. The medical school was established in 1875 and is located on the banks of the River Leith. The orginal Victorian buildings are now surrounded by modern glass and steel edifices that educate over 20,000 students of all disciplines.

I gave my guest lecture in the Department of Primary Care and Rural Studies. My subject was ‘Creating sustainable health care systems through the application of evidence and shared values’.

It was attended by the usual audience of health economists and public health staff, but also a PhD student from the Centre for Science Communication. Talking to her afterwards I heard that her dissertation was on the public perception of the evidence-base underpinning (or not) homeopathy. This was an important contact for me to make as the next stage of our local research project is to produce a film on a New Zealand health prioritisation issue. The idea is that the medium of film is the best way to engage the public in ‘tragic choices’ that occur in health prioritisation. In the UK, we have worked with the King’s College London Entrepreneurship Institute to produce a film ‘The Lottery of Devolved Cancer Care’.

Watch it here:

The film uses variation in access to expensive cancer drugs in countries within the UK as a relevant case study. It is based on the circumstances that led Ifron Williams moving from Wales to England to get his cancer treatment.

Over the next few days I had meetings with Paul Hansen, a health economist and developer of the 1,000 minds website that aims to make getting public preferences easier. Paul is an advisor to the WHO on decision making in antibiotic resistance (as well as a surfer). I also met with Peter Crampton the dean of the School of Medicine and pro-vice-chancellor of the Division of Health Sciences, who confirmed that our research proposals are aligned with Otago and New Zealand policy priorities. The next steps of the research programme are already beginning to take shape. Working in New Zealand while being in daily email contact with colleagues at King’s College London is odd. New Zealand is 13 hours ahead of London, so that I feel I am working today and tomorrow at the same time!

I had desk space in the office of the new Otago Global Health Institute, which is in the Commerce Building and is home to the Otago Business School (my host). This was an impressive building overlooking the rugby stadium and was just finishing a huge refurbishment. Each day I walked 30 minutes to work from my accommodation through the botanical gardens along the river bank.

Very different to my normal 30-minutes tube ride to work.

On my ‘day off’ I visited Larnach Castle (the only castle in New Zealand) built in 1871 by William Larnach, a banker and politician.

The location was chosen by his son while out walking because of the magnificent view over Otago peninsula – you can see why.

However, it did not give him much pleasure. After his first two wives died, and his third was rumoured to be having an affair with his son, he shot himself in a committee room in Parliament in 1889. His son later followed suit.

But today’s Dunedin is a much jollier place with students accounting for a large proportion of the population; 21.6% of the city’s population were aged between 15 and 24 at the last census, compared to the New Zealand average of 14.2%. There is a thriving music and arts and crafts scene and Dunedin was designated as a UNESCO city of Literature in 2014.

On the 16 November I attended the 2017 McAuley Oration delivered by Professor Mark McGillivray (an open lecture) held in Dunedin’s Public Art Gallery. A global expert on the causes of inequalities of health outcomes among developing countries, he is the 2017 William Evans Visiting Fellow at Otago University. Mark is currently a research professor in international development, at the Alfred Deakin Institute of Deakin University and former Chief Economist of the Australian Agency for International Development. The title of this lecture was ‘Converting economic growth into better health: which developing countries are better and why’. Mark is a health economist that concluded that his discipline could only take him so far and he has now supplemented his quantative approach with more culturally aware qualitative data collection. Like all good talks, it raised more questions than it answered.

On my last weekend on the South Island I travelled out to Lake Te Anau to cycle around its perimeter. Not much like my normal Richmond Park circuit, but not too bad.

My next meeting was to be in Wellington on the North Island to meet the PHARMAC (Pharmaceutical Management Agency) team. Arriving in Wellington I found that the PHARMAC offices are on the 9th floor of Simpl House in the centre of town, with magnificent views over the harbour. Wellington has been the capital of New Zealand since 1865 and government buildings reflect architectural preferences over time – for me the most the most beautiful remains the first – although the latest beehive is interesting.

There is much building going on in the government area, replacing older buildings with those more likely to be resilient to earthquakes, always an issue in New Zealnd.

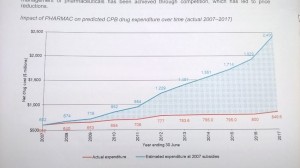

PHARMAC is a remarkable organisation. It is allocated a ‘Combined pharmaceutical budget’ by the government and has responsibility for ‘getting the best deal’ for new drugs for the population. This it has done very effectively over the years through robust methodologies and involving professionals and the public in its decision making. Reading their 2017 annual report reveals the scale of their success.

The shaded area between the graph’s lines indicates the total amount saved. This is the difference between the estimated spending without savings, and actual spending, around $NZ 6.0 billion. This is with a current annual combined pharmaceutical budget of $NZ 849.6 million. They have achieved this through competitive negotiating with big pharma. At an all-staff meeting, I presented the preliminary results of our project, which involved an assessment of their approach using the DMAT. Preliminary results showed how good they were. My research team will be following up with a meeting of PHARMAC’s patient group in the next few weeks. My visit coincided with another newspaper tirade against the rational approach that PHARMAC was taking highlighting (see below). It reflects that expensive cancer treatment is an issue everywhere and unfortunately the new New Zealand government is toying with the idea of a ‘cancer drugs fund’.

I described to them the NHS’s experience of using such an approach, and how short-term and unsustainable it is. During the meeting I discovered that one of the PHARMAC team had enrolled on the new King’s College London online MSc in Public Health, which I am helping to organise. What a small world. I will always remember this meeting – being introduced in traditional Maori manner, which included a call to order with a seashell and at the end being thanked with the Hongi.

I am now preparing to return to Brisbane, Australia, for a series of meetings with the Queensland Department of Health and Griffith University. But I could not leave New Zealand without a trip to the Tongariro national park and a tramp through the active volcanoes. First to Mount Ruapehu.

And then to Mount Ngauruhoe (which featured as the Mountain of Doom in Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings). Until 1975 Ngauruhoe has erupted at least every 11 months, including the 1954 eruption that lasted 11 months and disgorged six million cubic metres of lava.

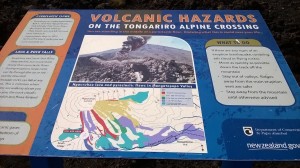

I read the warning sign carefully before ascending to the South Crater over the larval debris of the 1975 eruption.

The size of this crater is impressive (notice the people bottom left).

I then decided to descend as the clouds came in and the promised thunderstorms could be seen in the distance.

Leave a Reply